I am blessed with a couple of wetlands within an hour's drive from home. These wetlands are managed marshlands that municipalities use for water treatment and filtration, along with providing a preserve for migratory birds and other fauna and vegetations. Ducks and Canada geese are common visitors and I am especially fond of the geese because of the contrast provided by the black neck and the white band on their tail feathers, hence I model them often. My last blogs of Explorers and Reflection are examples of geese and wetlands being the source for my inspiration.

I've deemed these destinations as one of the few places that I could still go visit without violating Covid protocol. They are outdoor venues and I could easily avoid nexus with other humans by maintaining a 2 meter bubble. So I went to this 600 acre wetland that started out as a site for water waste disposal until enough complaints were registered to convince the city to mitigate the offense. Now it is home for a well managed eco-system punctuated with vast lakes and sloughs oozing from culverts and providing respite for domesticated and wild souls alike. I snapped a few photos for reference, and planned my next painting.

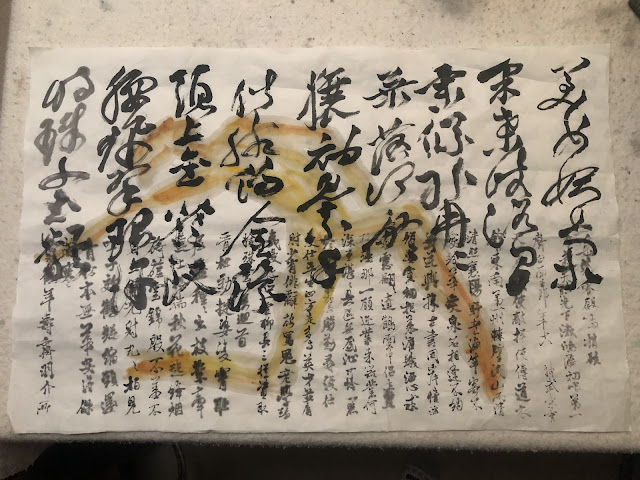

For this exercise I chose a Xuan paper that I bought for practicing brush calligraphy. This is not the maobian paper that I alluded to before but is yellow all the same. Unlike the more fibrous maobian this one is crisp and smooth. This paper is good for calligraphy because it is quite absorbent and the ink does not bleed easily. It can also withstand repeated rubbing from the brush without roughing up the surface into felt. The drawback for this paper is that it is not good at rendering ink tones and the lack of differentiation could make the painting sort of insipid. Nonetheless I picked this paper mostly because it has been a while since I last used it and I wanted to reacquaint myself with it.

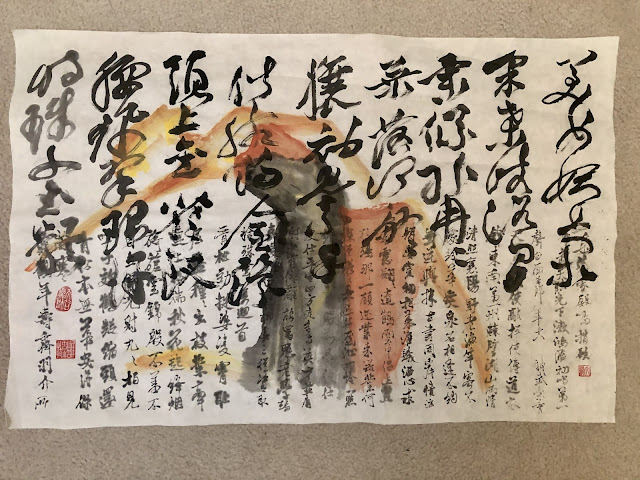

The yellow Xuan paper reminded me of the aged scroll paintings in museums, so I wanted to do this painting in a decidedly Chinese fashion.

I started out with the trees in the foreground. As far as I was concerned classical Chinese paintings had a very distinct way of depicting mixed shrubs and trees. Whenever one sees a grouping of trees being painted a certain way, one knows immediately that the painter had left a calling card to say that this was a Chinese painting.

Typically the trees would be of mixed species, often times conifers and deciduous together and assuming various pleasing poses.

The curved furrows left by tractors and the observation shed were points of interest when I visited the preserve, so I was determined to work them into my painting. Those were the landmarks that I associated with this particular wetlands preserve. I tried to adhere to the scheme of using just two colors and employed the classic dotting method of describing shrubs, stones or grass; and in some cases just for decoration and adding interest to the contour lines of the hill.

Modeling after the pair of Canada geese in my photo, I decided to use the middle void in the painting as the flight path for my geese. I loved the simple silhouettes of these birds. Their simple lines were conducive to treating them as Chinese fonts rather than birds. One could literally write them out instead of filling them in with ink.

I would be seriously remiss if I didn't set the stage for the hundreds of birds that swamp the preserve. They come and go in brigades of flopping dots in the distance and it was quite a sight to behold and to ponder if there was a vast body of water yonder obscured from my line of sight. Their cacophonic chattering broke the stillness of the area, without being annoying.

Almost all of these could be written with two or three strokes using the very tip of the round brush. It was fun to try to mix up the positions of the wings so they didn't look too unison. After all the fowls were not marching.

Was there any symbolism in painting paired geese flying towards the flock in the yonder? Could the grass be greener on the other side?

I had hoped for the formless brushstrokes in the distance, especially the strip on the upper right hand side to assume a much lighter value. I painted them with my brush wash, thinking that would be light enough. As it turned it, it wasn't. The culprit was the paper. This kind of Xuan paper is good at registering brushstrokes but not in showcasing ink tones.

The painting was wet mounted on a piece of regular white Xuan and then framed.

It provided me with something new to look at for a while.