I was invited to do an hour long demonstration at a local wetlands preserve. This was in response to my painting of the wetlands, which I had posted on this blog.

I quickly realized that Chinese brush landscape painting was not a good match for the en plein aire mode of painting. I needed a flat table and not a sketch pad or easel, and I needed a wool under pad for my Xuan paper. Something that would be harder to disguise would be my reluctance to do serious work in front of an audience. I felt that when I paint, it was my private moment, as I would be grabbling with my thoughts and feelings. I would feel naked and exposed if there was someone watching. Besides, I believe a lot of the classical Chinese landscape paintings were never about the actual sceneries, but rather stories about virtues, or euphemistic depictions of retreat. Thus the artists conjured up the scenery, almost like building a studio set for a movie, to get their point across.

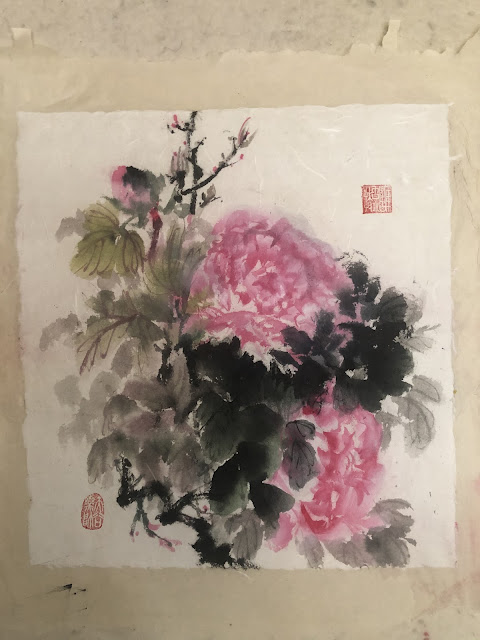

I thought a more appropriate approach would be to demonstrate how the Chinese round brush works. I would still try to paint the wetlands, or at least describe my thought process in arriving at the painting, but I thought a more dramatic demonstration was needed to call attention to the round brush. I decided to paint a peony flower. Painting a peony demanded the full employment of the entire brush, from tip to belly. The tip of the brush helped with creating the serrated edge of the petal, and the belly was used to describe the petal. Typically the entire brush would be loaded with titanium white and the tip alone would entertain a different color, depending on the color of the peony. Thus a single brushstroke rendered two different colors, with white being the belly of the brush and the colored tip would contrast with the adjacent void space to create the petal's edge. It would be easy to understand why the proper placement of the brush is of paramount importance.

Since I only had 60 minutes to attempt to explain and paint two different paintings, I thought I would cheat a little. I would have a painting of two peony flowers, with one of them already painted at home. In other words I would show up with a peony painting with one flower missing, so all I had to do would be to fill in the blank.

Obviously I needed to do my part, honing my peony flower skills. I didn't want to make a fool of myself.

I prepared two paintings of peony, done on different kinds of Xuan. I hoped to have a chance to illustrate how absorbency affected the presentation of the brushstroke.

I also planned a little theatre to get one of my points across, the fact that a painting on Xuan had to be mounted in order to be presented. I planned on squishing my finished peony painting as if to dispose of it, and upon disapproval, I would wet the painting down to relax the paper fibers, to impress the audience that the wetting down was the initial step to ready the painting for mounting.

My stop watch told me that I needed 15 to 20 minutes to paint the flower. That meant I had at least 30 minutes to do my landscape painting of the wetlands. Time management would be critical during the demonstration and this was how I prepared myself.

I invoked the Mustard Seed Garden manual as a witness to my interpretation of a mixed species woods, which the wetland had. I started out with the darkest ink value and proceeded to pan out my landscape.

I pointed out the fact that I wasn't constantly reloading my brush with ink, since I wanted to ink to gradually be depleted which led to a lighter value. This was how the different ink tones could develop naturally, if we allowed them. I would intersperse my talking strategically to allow my brush time to become drier as I yakked. I let the audience in on my ploys, so that they knew what I was doing at all times. I tried hard to dispel any myths or hypes to using the Chinese brush as an instrument to paint.

As the brush became drier, I proceeded with the Chuen technique, which granted more information about the rocks; and the Ts'a technique, which was rubbing with the dried belly of the brush to add texture.

I had time to add the obligatory pair of Canada geese, showcasing the calligraphy brushstroke. I punned the painting by adding in a pair of water buffaloes ( it would be strange to see water buffaloes in this neck of the woods) blaming it on the fact that this is the year of the Ox. It was just a spur of the moment jest to show what could be done with a few simple brushstrokes.

And so the hour flew by and mission accomplished.

And these were the results: