Aside from brush painting, music is my other vice. I was watching a recording of a masterclass given by a musician who had been immersed in the art for half a century. This particular segment involved a singer who sang 'Du bist die Ruh' for the workshop. This song was composed by Franz Schubert, lending his music to poem of a German poet. The soft and expressive song would demand more than perfect pitch and breath control from the singer, as I came to find out.

After the customary pat on the back, the master laid into the singer and sermonized the real issue.

"This is not an opera. Lieder! Lieder!"

What I find impressive is the master was contrasting Opera and Lied. I know these are different genres of works, but I believe ethnicity and culture play a huge role in defining opera and Lied as we know them in western music. When the master screams passionately "Lieder, Lieder" he is succinctly pointing out the narrow definition of a song form which Schubert happens to be perhaps the most famous Romantic composer. What was demanded of the student in the masterclass was not only the technique, but what was summed up in three words, "Give me Lieder"! We know immediately that this is music of a poetic German song form. The setting of a solo voice and piano does not necessarily reward a real projection of voice, but the piano and the singer share equal burdens to narrate the poetry musically.

Since beauty is in the eye of the beholder, can't we say songs are in the ears of the beholder also? Does music not function as a trigger, and the audience empathize and reverberate with their own life experiences, regardless of the quality of the performance? Yes, but then this defeats the purpose of conducting a masterclass on singing, does it not? Famous caveat from the master: "you can perform the music however you want, but this is what I suggest."

Thus one would not expect this Lied from Schubert to sound like a recitative from Don Giovanni. In this case, it has to have the personality of a Lied, which is foremost; and it has to sound like Schubert, and not Mozart. The singer needs to make belief that these are his precious and sensual words, and I am paraphrasing here. ' You are the calm, close the gate softly behind you; drive the pain out of the breast, my heart full with pleasure'. The drama is from within. The student however placed technique and accuracy above the cultural nuance of Lieder and failed to convey the delicate feeling of the Lied.

I had the pleasure of listening to a performance of Butterfly Lovers Violin Concerto, which has a synopsis based on a well-known Chinese folklore. The performance was by a violin soloist and accompanied by piano and not a full orchestra. Both the violinist and the accompanist performed beautifully and yet people were arguing whether the soloist was a Chinese, Korean or Japanese. And there were also comments to the effect that anybody could play Mozart or Bach, thus her ethnicity had no bearing to her performance. Is such a statement an extrapolation of "music transcends all racial barriers", or is it a misunderstanding and misinterpretation of the phrase? The argument here should be if the soloist in particular, was able to articulate the love tragedy resulting from hidden identity and arranged marriage in the old Feudal Chinese society. I have a recording of this piece performed on an Erhu, and I would go so far as to say that this Chinese bowed instrument is even more suited to portray the temperament of the composition. Perhaps the Erhu itself is unmistakably Chinese?? Not convinced? Imagine listening to a Wieniawski violin concerto played with an Erhu and you'll understand what I am attempting to convey.

Then I had the misfortune of listening to a clip sent by a friend of mine, of a western harpist playing a very famous Chinese tune on a western harp.

First of all, allow me to emphasize that I am not objecting to playing Chinese music with western musical instrument. Heaven knows I spent my childhood playing scores of Chinese tunes on my harmonica; and sometimes on a cracked violin in the fire-escape staircase ( to get better acoustics ). What I am having issue here is the interpretation of the Chinese music. My beef is not with the instrument, but with the musician.

Chinese music has not attained the global status of classical music in that classical music have been played millions of times in the modern world and have millions of recordings by different artists that one can easily emulate. I mean, no human alive today would know how exactly Mahler or Schubert played their works, other than markings of dynamics, expression, tempo and perhaps a few handwritten footnotes on the original scores. With subsequent invention of recording, there are tons of recordings of their works by the later musicians. After a while the collective styles of such playing become standards and different scholars chime in with their opinion of how a piece should really sound like. With claims such as "a Schubert pianissimo is not the same as a Chopin pianissimo", as if the claimant was by the side of the composers when the music was written. For a "catchy" Chinese tune to be performed properly, especially by a non-Chinese, it takes more than technique, but an immersion in the culture in order to distill the flavor of a Chinese song. It takes understanding. There just aren't as many examples of "proofs" of these Chinese songs that one can study and emulate. Often times western musicians become parrots; repeating musical phrases without necessarily understanding them. Of course the same applies to Asian musicians playing western compositions. Too often we generalize Chinese and the West as two distinct monoliths and do not want to invest the effort into a better understanding of the differences and similarities between the two, especially from a cultural and linguistic point of view.

The harp piece I listened to was played very energetically; bright and full of confidence; with all the attributes of a top-notch harpist. The harpist made percussive sounds by pounding on the wooden soundboard, as if to imitate a rim shot on a lion dance drum.

The Chinese piece that was played paints a very serene and calming scene, with the full moon tailing this little boat as it floats quietly along a river through mist, white sand and tree branches. The song asks the rhetorical question of whether the boater's lover (who was not in the boat) gets to witness the same moon as the boater and experiences the same inevitable journey of the boat gliding downstream, not being able to back paddle. They are drifting away from each other, with no assurance of a rendezvous. Time waits for nobody.

The song was about separation, longing and the passage of time. The gamut of emotions would not accommodate bright plucking, nor drum percussion effect. The moon light bathes the boat in misty air and shimmering water. The moon light was not a beam of lightning from claps of thunder. Granted the startling percussion might have sounded great in other songs, but to embellish this particular song with that is the worst kind of patronizing possible. Cultural differences become cultural barriers and nothing gets transcended. It is suspect of adding a cliché Asian element to make something more Asian. Regrettably, robing Marilyn Monroe in qipao does not make her Chinese. Is this an example of cultural appropriation, I wonder. Obviously music is a performing art and the artist has the freedom to interpret the music. Within the context of the piece, that is. I like to believe the era of playing some pentatonic dissonant riffs and finishing with a loud gong to portray Asian music or culture is behind us.

I was invited to a swanky American restaurant for their outlandishly priced Tasting Menu and one of the courses was Chinese Broccoli with Beef. An army of servers marched out in procession each clutching an iconic Chinese Take-out box, apparently to add drama to the presentation, and to convince the patrons that their meal ticket was well spent, and served the eight patrons seated at my table simultaneously. Chinese use a wok for stir fry because the curved sides of the wok offers a temperature gradient to modulate the cooking process and the concave bottom allows a reservoir of hot oil to sit in, extracting the flavors of garlic and ginger and what not, infusing the food with these subtle aroma. The beef in the Chinese Broccoli with Beef must be flashed in hot oil and not be smothered on a grill or a flat pan and dressed with Oyster Sauce. There is such a saying in the Cantonese vernacular regarding cooking, and it's called "Wok Hay". "Hay" is the Cantonese pronunciation for "Chi", thus wok energy. In other words, a person should be able to feel and enumerate the heat of the wok and the steps in throwing the ingredients together, with their palate. Obviously this pretentious restaurant knew convincingly little about the art of Chinese cooking. Anyways I asked the waiter to inform the Chef that his/her version of Chinese Broccoli with Beef was an insult to Chinese food, and if he/she wishes, I would be happy to give him/her a few pointers in the kitchen. Obviously I was ignored, and the restaurant didn't even have the courtesy to discount my exorbitant food bill.

Hence I submit ethnicity and culture are critical, albeit not always obvious, factors in shaping and understanding art and we appreciate and practice art based on our own inventory of sensibilities and prejudices. Different cultures have vastly different preferences in spices and tastes in epicurean art so why are other disciplines of art immune from cultural influences. Music in this case is inextricably tied to the language of the culture. It carries the cadence and inflection that is unique to the language in question. Perhaps I can draw similarities between speaking a native language or speaking with a foreign accent. I further submit that culture is more encompassing than ethnicity. This is the basis behind the term "banana", a derisive nomenclature used to denote people who are "yellow on the outside, but white on the inside". Culture affects everything we do, even in the arts.

Perhaps two examples of paintings can help to further illustrate my point. Vincent Van Gogh did a painting of a Japanese courtesan, based on a original painting of a courtesan by a Japanese painter Keisai Eisen. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Keisai_Eisen) Van Gogh tried to be faithful with the facial features and the headdress and the backward glance of the courtesan but took liberty with the kimono and the background. ( https://www.vangoghmuseum.nl/en/collection/s0116V1962) It wouldn't take but a cursory look to sense the different flavors in the two works, and which one is done by a Japanese painter. So the elephant in the room is, what are the defining factors, what are the clues. What makes Schubert different from Puccini; Van Gogh from Eisen; East from West.

Then an Italian missionary came to the East; China specifically, during the Qing dynasty and stayed for half a century. He painted a huge body of works, a lot of which borrowed the classical Chinese painting technique and ethos. Some of the exotic animals in the paintings and perhaps his not quite Chinese way of managing color and light values betrayed his ethnicity/culture but only to the discerning eye. Did his cultural biases and identity prevented him from adapting and adopting one hundred percent to the discipline of Chinese painting? One could say that his native tongue and "accent" in his painting gave him away. I am of course referring to Giuseppe Castiglione. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giuseppe_Castiglione_(Jesuit_painter)

I was using the example of Lieder to state my case of how ethnicity and culture might impact performing art. To draw an example from the East, falsetto voices from Chinese Opera, be it Peking or Cantonese is so unique that there could be no mistaking them as being absolutely uniquely Chinese. Even folk songs from different regions of China carry their own nuances and it will be just as plausible for a presenter of masterclass on Chinese songs to demand "Hungmei tone! Huangmei tone!" Thus it is just as crucial for the performer to know about the origin and style of this genre of songs, drawing a parallel to the "Lieder" example. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Huangmei_opera

Falsettos are commonly employed in both Western and Eastern singing. They are however vastly different in various cultures and they can identify the culture associated with them.

In visual arts "Chuen" is a technique that is almost ubiquitous in classical Chinese landscape paintings. I alluded to it in my blog "Gou, Chuen, Ts'a, R'an". It is the brushstroke used to impart texture to the landscape. The closest equivalence from the West that I could summon is perhaps the "hatching" or "cross-hatching" technique in drawing. The lines are used as a non-messy way of shading an object, and to a lesser extent, adding some texture. "Chuen" on the other hand, is used mainly to characterize texture, and to a lesser extent, shading. We have the elements of Ts'a (rubbing) and R'an (wash) to satisfy the shading part. It is interesting to note that shading is almost always judiciously applied and strong shading is actually not preferred in classical painting; it could be misconstrued as being a "dirty stain". I believe this is the reason classical Chinese paintings are very two-dimensional and flat looking; especially in portraits. The mark of competency, the Rembrandt Triangle of the Western ideal would have resulted in more than a brow beating.

Rote learning being a necessary evil in perfecting the craft of Chinese Brush painting, the Mustard Seed Garden has pages on the various styles of "chuen" by different masters and a compendium of some typical ways to "chuen", and the students are expected to pore over these materials and keep emulating until they "get it". With easy-to-understand names such as lotus leaf, draping hemp fibers, folded ribbons, axe hatching, sesame seed etc., the "chuen" brushstroke sometimes utilizes the tip of the brush only, sometimes the side of the brush is employed for effect. The accompanied pictures are taken from the book of Mustard Seed Garden showing the different "chuen" brushstrokes.

The presence of "chuen" brushstrokes in a landscape painting would be a good indicator that the painter has studied Chinese Brush painting methods because it is uniquely Chinese. Chinese brush painting like everything else cannot exist in a vacuum and as interaction with other civilization increases, a western and other Asian cultural influence is inevitable and hybridization ensues. However, even the relatively contemporary Qi Baisi and Zhang Daqian still employed such classical techniques such as "chuen". The contemporary impressionist Wu Guanzhong on the other hand only showed remnants of such practice. https://www.comuseum.com/painting/masters/wu-guanzhong/

In reviewing my old paintings, I realized that I skimmed on the "chuen" aspect of my paintings and relied on the rubbing and wash elements to render the dimensional feel, and I definitely would not call myself a contemporary impressionist!

I can feel the conductor of Classical Chinese Brush MasterClass barking at me: "Chuen! Chuen!"

There are only two reasons for that, being inept and being lazy. Or could it be that I am westernized?

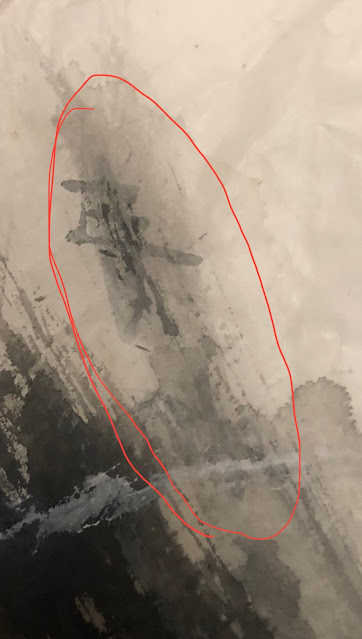

Since I don't have anything better, or more meaningful to do, I decide to paint over one of my finished paintings and build up more "chuen" brushstrokes. I have nothing to lose but a piece of paper should I fail.

So I forge ahead with the ribbon and hemp fiber and sesame seed "chuen" strokes and build on the areas that had been rubbed and washed previously.

The right side of the painting is now much darker, due to the additional brushstrokes. This makes a even stronger contrast to the landscape across the water, and this is the effect I am looking for. The precipitous rock face is now convincingly in the shadow, against the backdrop of the salmon colored sky. The added "cheun" most definitely gives the landscape loads of texture, giving it a three-dimensional appearance. One might say that it has pop now. But then I might have committed the crime of rendering my painting too dimensional, too forceful; in the realm of classical virtues anyways. Perhaps my work is more of a elevator music variety than a Lied. Perhaps this is the reason some of my peers shun me.

I decide to reign myself in and do some honest practicing on the technique of "chuen". Practice makes perfect, I am told.

I must say my homework looks a lot more "Chinese" than my previous works. My mountain lobes look very classical and Chinese. So has my ethnicity or culture changed?

I've been overseas for over half a century, so for all practical purposes I am a "foreigner" steeped in western culture. I speak English everyday, at my job and socially and yet I can't shake my Chinese accent. I should have become a "banana" like my children but somehow I didn't. What I've become is a over-ripen banana, yellow on the outside and a mishmash of white and yellow on the inside. Does that affect how I interpret the world, and arts?

Perhaps I am just confused.