I am an enthusiast of Chinese Brush Painting and I would like to share my trials and tribulations in learning the craft. I want to document the process, the inspiration and the weird ideas behind my projects and to address some of the nuances related to this dicipline. I hope to create a dialogue and stir up some interest in the art of painting with a Chinese brush on Xuan. In any case, it would be interesting to see my own evolution as time progresses. This is my journal

Sunday, July 25, 2021

Dare to change, Vive ya

Sunday, July 4, 2021

Putting old latex paint to use

I was trying to clean up my garage and found some latex paint test samples. Since the chemicals collecting stations had been shut down due to the Covid situation, I thought I would find some way to use them up. I wonder if I could paint with them.

Found my old Ram painting at hand and that was as good a guinea pig as any, for my latex paint experiment.

I started out with the ram on the bottom. The first thing I noticed was the ability for the paint to hide everything.

The second thing I found out was how thick the paint was, and it rendered my soft hair brushes totally limp, with no ability to rebound. Now I understand why the paint stores sell stiff nylon bristle paint brushes. I was just glad that I didn't use my "nice" brushes for my experiment and I was also quick to clean my brushes out the moment I was done with one section.

I really wasn't planning on documenting the whole process so I didn't take pictures along the way. I only had the finished experiment to show here:

I also painted a couple canvas in red and wanted to dry mount a couple of my zodiac animals on them.

I did the Ox painting first and quickly learned that the paper I painted on was too thin and allowed the red from the canvas to shine through. That was a bummer.

It was a fun way to re-purpose some old latex paint, canvas and old paintings.

Thursday, July 1, 2021

Finishing Multnomah Falls

After a couple of weeks looking at my bouquets of flowers adorning the Multnomah Falls, I felt less offended by the painting. Granted it wasn't what I had in mind but it had its own nuances.

Anyways I needed to go through with what I had imagined originally. So I liberally applied my cinnabar to showcase the fall foliage. They were no longer these timid dots but a full blown fall color with aplomb.

Friday, June 25, 2021

How does that grab you

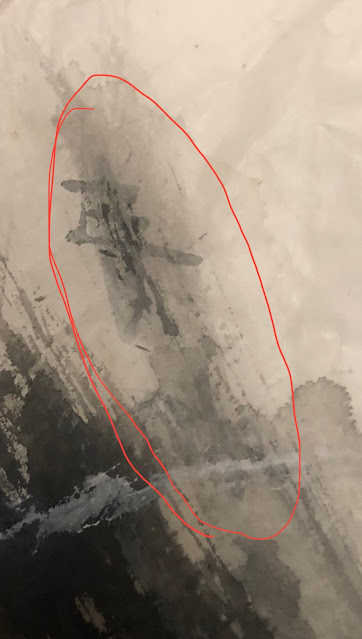

I was trying to clean out my room and spotted something in the pile destined for the paper recycle bin. It was a painting from that I had started long ago but never finished. More like a doodling than a painting actually.

I felt the urge to add something to the painting. I had nothing to lose, it was half way out the door already. Anyways I finished it in the wee hours of the night and took a picture. What came to mind was the word Avatar. How about the Dawn of Times

So I took another picture the next morning, under normal daylight. A different white balance gave the painting a different personality.

Wednesday, June 2, 2021

Multnomah Falls

A major part of the historic Old Columbia River Highway was reopened not long ago, iteafter the landslide was cleared away and damaged section repaired. One could again drove to the many different falls dotting the highway. I recently painted the Vista House from the Columbia River Gorge, and was itching to paint the Multnomah Falls again.

I must have tried 3 or 4 different iterations of the Multnomah Falls over the years and I realized that my approach to this subject matter was different each time. I was more or less bound by the Chinese brush doctrines before, despite my inadequacy and being a poor student. I decided that I was going to rid all shackles and just paint this time.

I chose a rather thick, very fibrous "leather" Xuan this time. The fibers added texture and the thick leathery Xuan was absorbent, yet allowed the water to float a bit before being assimilated, not unlike watercolor paper.

The first rule I broke was to paint the water of the Falls. Normally I would define the water with the negative void space. In fact from what I was taught, the using of a white color to paint water was frowned upon. Treating water by painting it was quite liberating. In fact that was the very first thing I did, painting the water of the Falls, using lighter grades of ink intermingled in the titanium white streaks to signal a flow.

As for the cliffs from which the falls clung to, I used broad dabs of a mixture of colors, setting the base tones of the landscape and accenting particular colors to set the stage for the features that I planned to portray, i.e. mist, sky, top of the cliff etc. At one of my painting lessons, I was asked to randomly splash red and phthalocyanine blue onto the Xuan paper and then tried to make some sense of the resulting splash pattern and create a landscape from these two colors. I was employing the same principle with this painting, albeit the mix was a lot tamer. There were tons of overlapping brushstrokes, totally against the etiquette of not covering the previous brushstrokes as prescribed in a proper Chinese brush painting method. Again, this was liberating. I felt like I was doing an oil painting, and my thick leathery Xuan was a perfect cohort and took the abuse with such poise.

Oh, did I also confess that I cheated, well sort of, by sketching out with charcoal my Falls and the bridge etc. on the back of my translucent Xuan first? It was much easier to follow the lines and paint on the top side, especially for the water.

I think some of the charcoal from the back of the paper might have gotten incorporated into the paper once the moisture from the top side reached it. This actually worked out great, especially as far as the edges of the Falls and the silhouette of the bridge was concerned. It added depth to the brushstrokes and rendered a 3-D effect. Something I might need to explore in the future and warrant further experimentation.

The painting actually didn't look half bad at this point. I could have passed it for a blurry, mystic interpretation of the Falls? But that wasn't what I set out to do, so forge on!

I intended a fall color for the Falls, thus the yellow dots were the base color for my cinnabar.

I seemed to have run into a dead end. I didn't like the painting at this stage. It felt like the landscape was dotted with bouquets of flowers instead of a fall foliage. I wished I had stopped at the stage when the painting looked kind of fuzzy.

Time to rest. Give the painting a rest, Give myself a rest.

Monday, May 17, 2021

Mounting my demo pieces

I decided to mount the two pieces of paintings from the demo session at the wetlands. I happened to pick the very fibrous and thick "leather" Xuan as the paper to paint on that day, so the mounting should be relatively easy.

I would be wet mounting them as usual. I've discussed and debated with people concerning the dry silicone mounting method. If I brought my hubris to the table, I would have said that the dry method was for those who either didn't know how to, or lacked the skill to do the wet mount. I have personally tried both methods, and have even tried ironing commercial food wrap as a binder, but I've always preferred the wet mounting method, despite the many cumbersome steps it requires. Call me a snob but there is a je ne sais quoi quality about a starched, perfectly stretched and flat piece of work from the wet mounting that dry mounting can never hold a candle to. I would however use dry mounting if I chose to present my painting mounted under a piece of glass. In that case I would have used the very thin, semi-sized "cicadas wing" Xuan as my painting paper, and the added reflective layer of the silicone binder provides a seemingly ephemeral, yet perceptive richness to the color and the translucent paper when viewed through the glass pane. I guess that's what linseed oil does to color pigments.

The doors on my storage cabinet are covered with smooth mylar, perfect as a mounting surface.

Being a good student of wet mounting, I even included a blow hole provision on the right side of the mount. Supposedly one is to blow through this passage such that the wet painting is lifted from the mounting surface ever so slightly, to prevent sticking from any bleed through starch. I personally have found this to be more academic than practical. The lifting seems to occur around the blow hole area only. Perhaps I am not doing this correctly or that I need more than one blow hole. In reality I've almost never encountered any paintings stuck on the mounting surface when dried.

Depicting a straw connected to the blow hole

The dried paintings were taken off the mounting surfaces and stamped with my seals and were ready to be framed.

Saturday, May 1, 2021

Demo

I was invited to do an hour long demonstration at a local wetlands preserve. This was in response to my painting of the wetlands, which I had posted on this blog.

I quickly realized that Chinese brush landscape painting was not a good match for the en plein aire mode of painting. I needed a flat table and not a sketch pad or easel, and I needed a wool under pad for my Xuan paper. Something that would be harder to disguise would be my reluctance to do serious work in front of an audience. I felt that when I paint, it was my private moment, as I would be grabbling with my thoughts and feelings. I would feel naked and exposed if there was someone watching. Besides, I believe a lot of the classical Chinese landscape paintings were never about the actual sceneries, but rather stories about virtues, or euphemistic depictions of retreat. Thus the artists conjured up the scenery, almost like building a studio set for a movie, to get their point across.

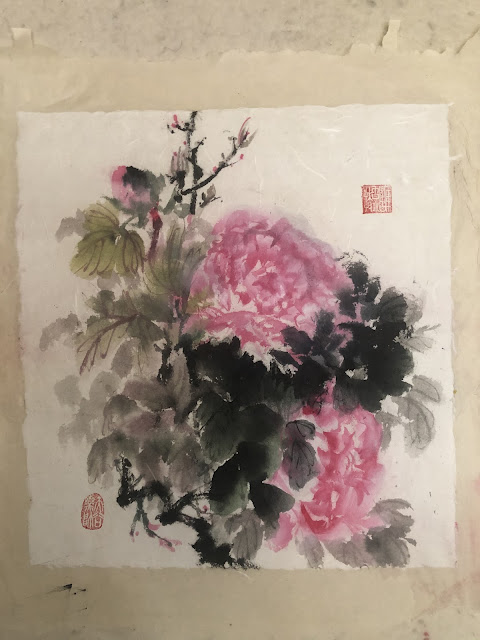

I thought a more appropriate approach would be to demonstrate how the Chinese round brush works. I would still try to paint the wetlands, or at least describe my thought process in arriving at the painting, but I thought a more dramatic demonstration was needed to call attention to the round brush. I decided to paint a peony flower. Painting a peony demanded the full employment of the entire brush, from tip to belly. The tip of the brush helped with creating the serrated edge of the petal, and the belly was used to describe the petal. Typically the entire brush would be loaded with titanium white and the tip alone would entertain a different color, depending on the color of the peony. Thus a single brushstroke rendered two different colors, with white being the belly of the brush and the colored tip would contrast with the adjacent void space to create the petal's edge. It would be easy to understand why the proper placement of the brush is of paramount importance.

Since I only had 60 minutes to attempt to explain and paint two different paintings, I thought I would cheat a little. I would have a painting of two peony flowers, with one of them already painted at home. In other words I would show up with a peony painting with one flower missing, so all I had to do would be to fill in the blank.

Obviously I needed to do my part, honing my peony flower skills. I didn't want to make a fool of myself.

I prepared two paintings of peony, done on different kinds of Xuan. I hoped to have a chance to illustrate how absorbency affected the presentation of the brushstroke.