The traditional Chinese landscape painting model would have a cluster of trees, each with a different foliage, to establish spatial relationship. When you look into the Mustard Seed Garden Manual ( Jieziyuan Huapu ) you'll find pages and pages of methods on painting different foliage, i.e. dots, lines, circles, triangles etc. and methods of painting trees and branches, assigning description such as crab claw, deer antler among other things. Typically you would see branches and foliage of different species woven together, allowing various degree of obscurity to represent which tree is in front of the other. Such separation would be more difficult to show in a homogeneous group.

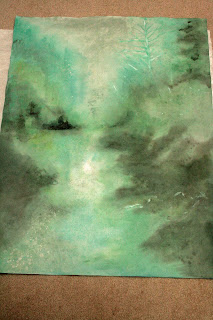

cluster of mixed trees

When I painted my Multnomah Falls (Multnomah Falls Again blog), I utilized such an arrangement. We would coin this layout as painting "mixed trees", not that they are the real indigenous species, but are more likely to be fictitious sets.

Since I was playing with my alum solution again, I decided to experiment with the technique of expressing spatial relationship again. I wanted to paint just one tree, but the branches themselves have to showcase the perspective. I have the image of this huge tree in Kowloon Park. The branches are so huge and convoluted that they actually rest on cement columns for support. My challenge is to establish the relative position of the branches without resorting to different foliage.

For this exercise, I was using left over pigments from my dish ( red and blue and yellow ) . My brush was first saturated with alum solution, then dipped into the color wells. Ink was added to attain the desired black levels. The paper I used was a remnant hemp paper ( not the usual raw Xuan ) and this turned out to be less than desirable for this purpose.

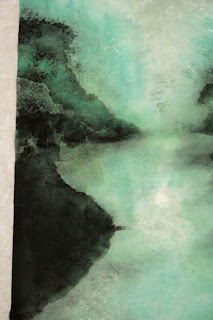

boneless strokes rendered in alum+pigments

the back side of image above, white patches are caused by alum

I then flipped the paper over and used the backside as the front of my painting. I did that to try to exploit the alum solution. Brush strokes done with alum and pigments would show a minute clear margin around the strokes, and is more prominent on the back side. This effect is usually quite apparent when using raw Xuan, but did not show up quite as well with the hemp paper. I suspect the paper is semi-sized to begin with, because the color sits on it for a while before being soaked into the paper. I used some diluted titanium white along the edges of the brush strokes to mitigate the apparent lack of clear margins. On the outside of the titanium white, I lined in with ink. Essentially, I started out with a boneless brushstroke of the branches and then use titanium white and ink as my Gou step (refer to my blog on Gou, Chuen, Ts'a, R'an blog on June 24, 2011). That was followed by Chuen and Ts'a with the dried belly of the brush to give texture. The final step was R'an with a wash to add shading.

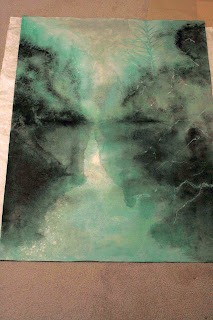

ink line outside of margin

Gou, Chuen, T'sa, R'an

It is important to tread with a light foot (hand) in the Gou step. The lines need to be loose and do not need to be continuous; try to feel it. Pay special attention to the junctures where branches cross. Allow enough spacing to the back branches to give depth ( refer to More Than Just Broken Lines blog on March 29, 2012). The fatter and lighter imprint of brush strokes from the reverse side of the paper gives a shadow effect to the narrow Gou outlines, giving the branches a more 3-dimensional feel.

keep the Gou lines loose and spirited

fatter imprint from the reverse side adds body

The final product now shows depth, texture and a concrete representation of the location of the different branches.