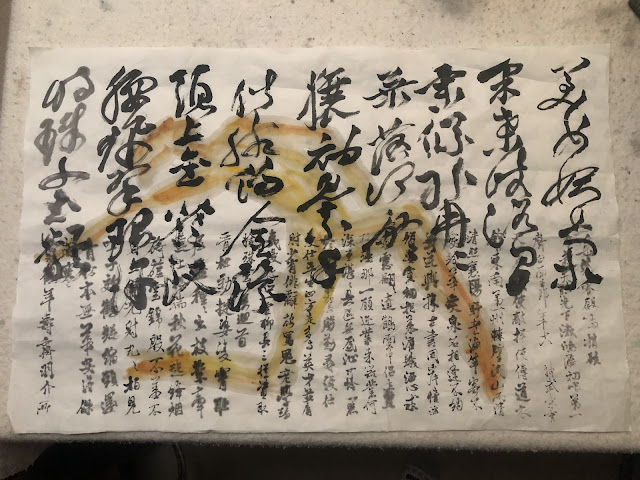

After four attempts at painting my ox, realizing incremental improvement after each trial, I was left with a void, a less than satisfying feeling, still.

I couldn't quite pinpoint what prompted this notion. Perhaps my painting didn't tell a story, like my Year of the Rat or Year of the Rooster paintings did. Perhaps the ambience of the painting wasn't befitting a New Year's theme and was too monolithic. Or could it be that it wasn't "Chinese" enough, since I was ruminating the connotation of whether a painting is "Chinese" or not. How could I translate a sentiment that is beyond my capability to be succinct about; beyond my wisdom to verbalize.

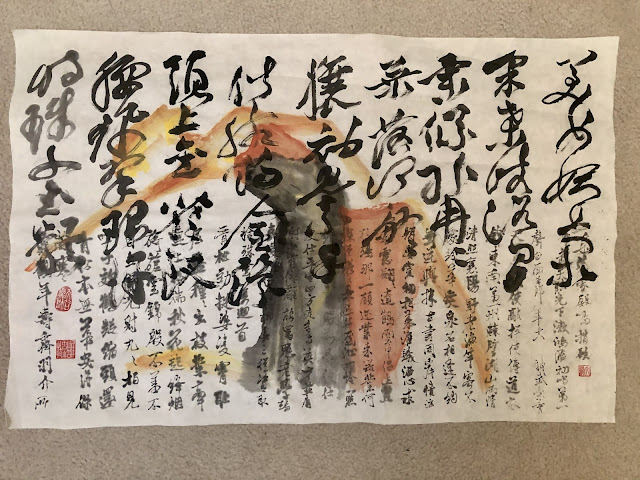

One thing that was within my reach was to try to tell a story with my intended painting, beyond just a representation of vigor and might. My reason to start painting the ox painting was ostensibly due to the arrival of the Year of the Ox, but also the desire to expel anything that went awry during the Year of the Rat. My painting of the Ox could be the rostrum for such proclamation.

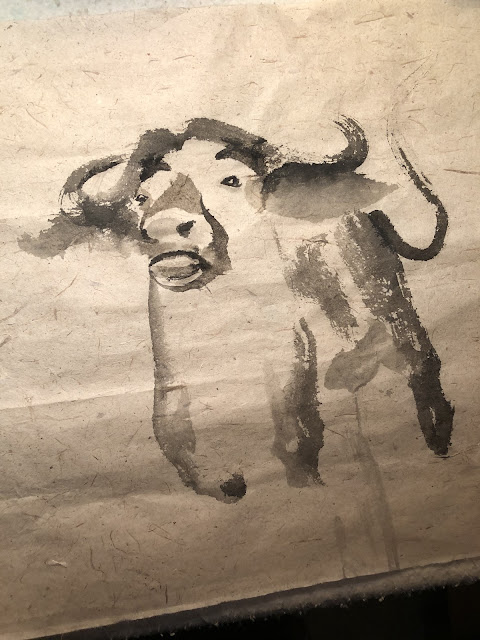

Thus my painting would tell the story of an ox evicting the rat. More than merely a changing of the guards.

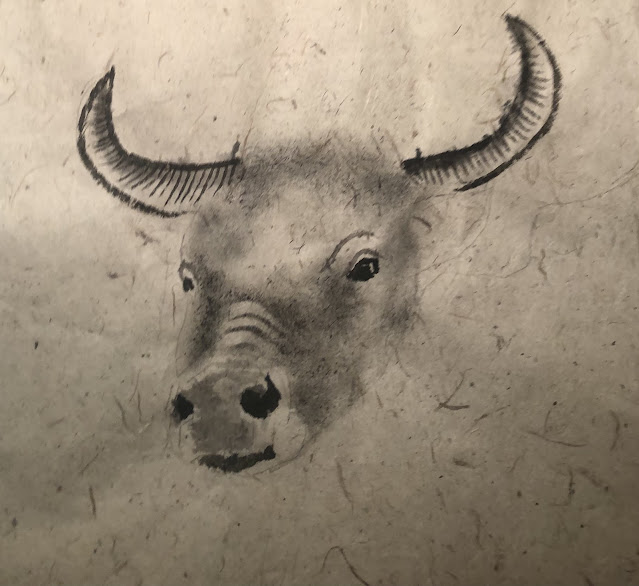

Honestly I was getting a little tired of painting the same ox over and over again. I was never a good student because I loathed practicing. I always wanted something fresh, and fast. So for this painting I substituted a stiff hair, totally worn round brush for my regular round brush. I intended to rely on the dry ink mottling, with the help of the regular wash, to render the shading of my beast. A worn out brush is ideal for this purpose since its hairs form hundreds of points rather than the one single point when new. Thus I never threw out my worn brushes. I was hoping the dry ink mottling would add interesting texture and credibility to my ox. I trust subconsciously I was trying to emulate the smudging of a charcoal painting. Also I've read somewhere that part of the intrigue of Mona Lisa was the fact that there were no harsh lines on her face, adding to the organic expression of facial emotional contents of a human. Regardless of my true motivation, I was ready to enter the game.

I cut out a stencil to help depict the skin folds on the nose ridge, adding interest to the structure.

My urge to keep the painting process fresh and interesting had led to this experimentation. I must admit, I was like a school kid finding a dollar bill on the playground, pure joy!

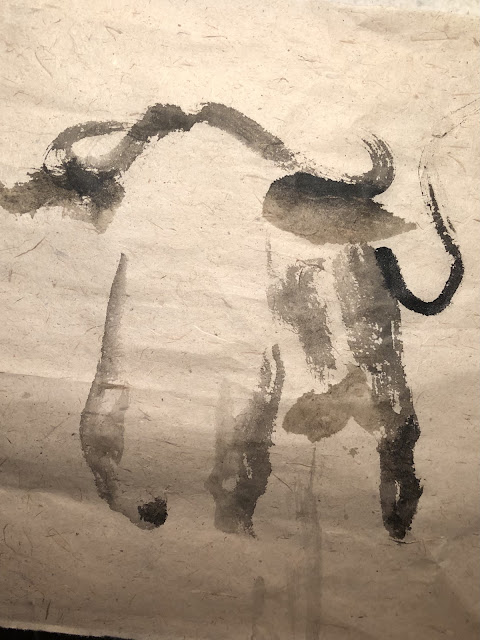

Chinese or not, here I come. I expanded the stencil technique to add skin folds to the back of the ox.

Using a rather dry brush, I scriggled lines to represent water, in which my ox was half submerged.

The water solved two problems. It hid the legs of the ox, so I didn't have to be concerned about their placements. It also took up a large portion of the painting; less for me to paint.

The other protagonist in this story was the rat. I painted it white to make it stand out a bit but it was still difficult to see due to its size. Incidentally I painted last years rat in white, so there is continuity in my story now. I had the rat scurrying across the water, away from the ox, as if it was being chased away.

I am calling it quits. This is my final attempt at the ox painting, and I named it

"The Ox evicting the Rat"