Two of my paintings needed mounting and framing. They got juried into an exhibition. One of those was the one I named Oblivious; the "have eyes but won't see" painting. This was especially uplifting, as I felt vindicated, after being rejected twice by other venues. I was told by the curator that the reason for rejection was "the faces are not familiar to the west". I didn't know I was signing up for a course in Bovine Scatology! On the other hand, it exemplified the caliber of the show! Might as well!

Again I mounted them in the Suliao Xuan Ban fashion, and again I stained my frames with the same ink I painted with to achieve that tonal continuity between the painting and the frame.

I devised a new method to combat the bubbles that popped up under the paper. This was probably due to defects in the silicone layer. I used a stress ball as a roller to help tamp the Xuan onto the heated silicone surface. The ball was very pliable and made even contact with the surface when pressed. The added bonus was that I got to massage my acupressure points in my palm (wink, wink).

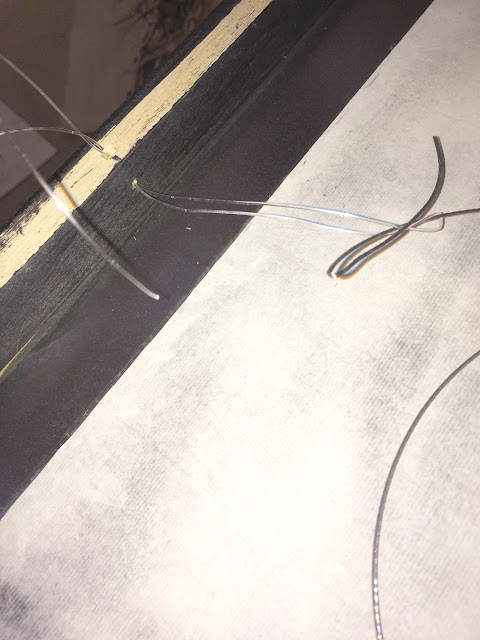

I modified my hanging string this time.

I had used the regular metal picture wires before for the cross string. That was until my confidant pointed out to me that the wire was visible through the clear margin that I had painstakingly designed. My reason for that clear margin ( in lieu of a traditional mat) was to exaggerate the float effect of the painting. I also wanted to free the painting from the immediate enclosing feeling of the frames. So after having these thoughts executed into the design of the setup, I ruined it by allowing the viewer to see a metal wire through the acrylic pane. That was more than a fly in the ointment. This is a mistake that I often make. I am always in a hurry to finish a project that I would not think through the last few steps. I will write these steps off as being incidental and trivial and not critical. I just have no patience; too eager to call it done. That's the bane of my life.

To make the hanging wire less visible, I thought of the leader system of fishing hooks, harking back to the days when I would ford the streams and fish a little bit. I would use the regular metal hanging wire, but instead of the entire length, I would tie both ends to clear fishing lines. This way the clear fishing lines were under the clear acrylic margin, and were not readily visible. The reason I did not use fishing line for the whole length to begin with was because the length of the wire was too long in the landscape setup. The weight of the wood frame and the plastic caused the wire to stretch too much, resulting in the hanging hook visible above the frame. That destroyed the presentation. I wanted to frame to just appear on the wall, without any obvious means of hanging or attachment.

I drilled a 90 degree angled passage in the narrow wood frame and passed my fishing line through that. I then tied a huge knot; one that was big enough to not slip through the tiny hole, thus securing the line. I then tied the clear fishing line to the metal hanging wire. The beauty of this design was that no hanging hardware was required, and the hanging hook would be hidden by the painting itself.

This is how the finished product looked on the wall.

No visible hooks or wires!

I am an enthusiast of Chinese Brush Painting and I would like to share my trials and tribulations in learning the craft. I want to document the process, the inspiration and the weird ideas behind my projects and to address some of the nuances related to this dicipline. I hope to create a dialogue and stir up some interest in the art of painting with a Chinese brush on Xuan. In any case, it would be interesting to see my own evolution as time progresses.

Monday, February 6, 2017

Thursday, February 2, 2017

Sulio Xuan Ban and Xuan Boo in action

I have mentioned my unique ways of mounting Chinese brush paintings in my blogs. Xuan-Boo is how I mounted Xuan on canvas. Suliao Xuan Ban is mounting Xuan on plastic.

I have been labelled as being "gimmicky" by the camp of traditional brush artists. In my defense, I was motivated by circumstances.

The traditional way of mounting Xuan on paper or silk is great. Unfortunately, having paintings mounted in a scroll format demands skilled craftsmanship. There just aren't too many of these floating around when one is in a town where such crafts are rather obscure and esoteric. I could have mounted the Xuan on paper and present it in a picture frame, but I see two limitations. The first one being the glass frame imposes a glare, and museum grade non-glare glass is not economical and not often available in the odd sizes. The second factor is that the painting loses the vivaciousness once dried. I like the wet look so much better.

When I first fooled around with Xuan-Boo, I was instantly attracted to it. The texture of the canvas and the color luminosity being restored by applying the protective gel. The application of gel was to protect the surface of the painting from the usual indoor elements. I had no idea that it added to the depth of the color. That truly was serendipity in action.

I really like a lot of the "metallic" prints of photographs and the way they were presented. No frames, just sort of floated from the wall. That was my inspiration for devising the Suliao Xuan Ban technique. I compromised on the absence of frame by creating a clear margin around the painting, allowing it to float on the display wall.

There are ongoing debates about the merits of wet versus dry mounting. Chinese wet mounting has been the gold standard in the traditional way. Having done both I would say that a nicely done wet mounting is superior to the dry mounted one. This is especially apparent when one can hold that piece of work in your hands. It just feels organic and not mechanical. A point that the wet mounting camp stresses is that a dry mount is irreversible. Museums have been know to re-mount a piece of deteriorated ancient work and restore the painting. This would not be possible with dry mount. But then again, how many pieces of our works gain immortality? Of course the main reason for dry mounting is that the execution generally requires less skill, and is definitely not as time consuming.

Some people at the local galleries balk at the idea that the painting is mounted. They asserted that the painting must retain the flexibility of being able to be presented in the frame of the customer's choosing. In other words, the consumer might not like the way I presented it, and would need to replace the frame. They are in effect paying money for the painting itself and nothing else.

Recently I had a chance to present exclusively my two methods of mounting at an exhibition. I did that obviously to satisfy my own biases and I really don't expect the audience to know one way or another.

It was gratifying to see how my presentation was so vastly different from everybody else's.

These are paintings done in the Xuan-Boo fashion:

These are done in the Suliao Xuan Ban fashion:

Call me a goofball, call me a gimmick, I'm just not satisfied with the status quo.

I have been labelled as being "gimmicky" by the camp of traditional brush artists. In my defense, I was motivated by circumstances.

The traditional way of mounting Xuan on paper or silk is great. Unfortunately, having paintings mounted in a scroll format demands skilled craftsmanship. There just aren't too many of these floating around when one is in a town where such crafts are rather obscure and esoteric. I could have mounted the Xuan on paper and present it in a picture frame, but I see two limitations. The first one being the glass frame imposes a glare, and museum grade non-glare glass is not economical and not often available in the odd sizes. The second factor is that the painting loses the vivaciousness once dried. I like the wet look so much better.

When I first fooled around with Xuan-Boo, I was instantly attracted to it. The texture of the canvas and the color luminosity being restored by applying the protective gel. The application of gel was to protect the surface of the painting from the usual indoor elements. I had no idea that it added to the depth of the color. That truly was serendipity in action.

I really like a lot of the "metallic" prints of photographs and the way they were presented. No frames, just sort of floated from the wall. That was my inspiration for devising the Suliao Xuan Ban technique. I compromised on the absence of frame by creating a clear margin around the painting, allowing it to float on the display wall.

There are ongoing debates about the merits of wet versus dry mounting. Chinese wet mounting has been the gold standard in the traditional way. Having done both I would say that a nicely done wet mounting is superior to the dry mounted one. This is especially apparent when one can hold that piece of work in your hands. It just feels organic and not mechanical. A point that the wet mounting camp stresses is that a dry mount is irreversible. Museums have been know to re-mount a piece of deteriorated ancient work and restore the painting. This would not be possible with dry mount. But then again, how many pieces of our works gain immortality? Of course the main reason for dry mounting is that the execution generally requires less skill, and is definitely not as time consuming.

Some people at the local galleries balk at the idea that the painting is mounted. They asserted that the painting must retain the flexibility of being able to be presented in the frame of the customer's choosing. In other words, the consumer might not like the way I presented it, and would need to replace the frame. They are in effect paying money for the painting itself and nothing else.

Recently I had a chance to present exclusively my two methods of mounting at an exhibition. I did that obviously to satisfy my own biases and I really don't expect the audience to know one way or another.

It was gratifying to see how my presentation was so vastly different from everybody else's.

These are paintings done in the Xuan-Boo fashion:

These are done in the Suliao Xuan Ban fashion:

Call me a goofball, call me a gimmick, I'm just not satisfied with the status quo.

Tuesday, January 31, 2017

Painting Rooster

This is the year of the Rooster so that explains my motivation for painting the rooster.

It is customary for a lot of Chinese businesses to print and give away complimentary calendars to celebrate the New Year thus an example of a rooster painting would not be difficult to come by. I would say that most of these paintings would have the quintessential arrangement of a rooster with other elements of Chinese brush painting; such as wisteria, chrysanthemum, bamboo, Taihu stone, peony.

I want to present my bird in a stylized manner. I want to emphasize the pose as being intrepid, arrogant. My personal perception of a sassy bird is one with an attitude, one that struts with swag and raises its tail feathers like a proud peacock. I also want to dispense with the usual incidental elements that I mentioned earlier. I wanted my painting to tell a story, instead of a still life arrangement.

I don't want to be too far from the truth with regards to anatomical features, so I looked at a few pictures of the head, paying attention to the comb and the wattles and how they relate to the eye and the beak.

I did my practice exercise

I just realized I left out the ear and the ear lobe!

I also wanted to get the feet right, Not trusting my memories of years of munching on chicken feet, again I gathered reference material; and realized that a painting with a 5 or 3 toed rooster is an erroneous depiction.

I sketched out the pose for my bird first, and went to work. I chose a non-bleached paper with visible strands of fiber, for that informal, home made, folksy feel.

I filled in the plumage

and adorned it with my attitude piece de resistance, the rooster tail. I painted it high and proud.

I thought the lone cock is too austere for such an auspicious occasion and a companion is needed. I thought for a long time about the composition and I arrived at needing a hen that faces the other direction. I want the birds to be doing do-si-do and not promenade. I think this arrangement carries more theater.

I found this picture on the net

My wish was granted.

I used the shaft of my brush to extend a line of sight from the rooster's eye and placed the hen there. I needed to show what he was interested in. This is a key element in establishing the relationship between the main characters.

Not afraid of running the risk of being trite or pedantic, I decided to complement the rooster and the hen with a family.

After I texted this image to my confidant, I was reminded that the 2 chicks were placed too evenly and suggested I add another member to the brood.

I am thankful for that advice.

I like the emotion and the energy this painting portrays. I can sense the movement and interaction in this family. The parents' focus was in each other, and the chicks begged only from the mother. Of course I am biased.

What I don't like is the rooster looked a little slim to me. I would love to have painted a fuller lower body. I think I painted his foot wrong. Had I painted his toes facing the viewer, it would have suggested a body turning towards the viewer, thus presenting a narrower girth.

The angle of the leg stance did not seem right either. It was too straight. I was so carried away by the thought of standing pound and tall that I ignored the natural stance. Had I superimposed the leg skeletal structure onto my rooster to begin with, in my mind at least, I would have avoided this mistake.

The above illustration shows the relative angles of the femur, tibia and the tarsometatarsals of the rooster's leg. It is obvious that the leg does not go vertically up and down. Just to prove my point I digitally moved the leg to the new position. I think it looks much better this way. What a difference 9 degrees off center makes!

Again, Happy New Year!

It is customary for a lot of Chinese businesses to print and give away complimentary calendars to celebrate the New Year thus an example of a rooster painting would not be difficult to come by. I would say that most of these paintings would have the quintessential arrangement of a rooster with other elements of Chinese brush painting; such as wisteria, chrysanthemum, bamboo, Taihu stone, peony.

I want to present my bird in a stylized manner. I want to emphasize the pose as being intrepid, arrogant. My personal perception of a sassy bird is one with an attitude, one that struts with swag and raises its tail feathers like a proud peacock. I also want to dispense with the usual incidental elements that I mentioned earlier. I wanted my painting to tell a story, instead of a still life arrangement.

I don't want to be too far from the truth with regards to anatomical features, so I looked at a few pictures of the head, paying attention to the comb and the wattles and how they relate to the eye and the beak.

I did my practice exercise

I just realized I left out the ear and the ear lobe!

I also wanted to get the feet right, Not trusting my memories of years of munching on chicken feet, again I gathered reference material; and realized that a painting with a 5 or 3 toed rooster is an erroneous depiction.

I sketched out the pose for my bird first, and went to work. I chose a non-bleached paper with visible strands of fiber, for that informal, home made, folksy feel.

I filled in the plumage

and adorned it with my attitude piece de resistance, the rooster tail. I painted it high and proud.

I thought the lone cock is too austere for such an auspicious occasion and a companion is needed. I thought for a long time about the composition and I arrived at needing a hen that faces the other direction. I want the birds to be doing do-si-do and not promenade. I think this arrangement carries more theater.

I found this picture on the net

My wish was granted.

I used the shaft of my brush to extend a line of sight from the rooster's eye and placed the hen there. I needed to show what he was interested in. This is a key element in establishing the relationship between the main characters.

Not afraid of running the risk of being trite or pedantic, I decided to complement the rooster and the hen with a family.

After I texted this image to my confidant, I was reminded that the 2 chicks were placed too evenly and suggested I add another member to the brood.

I am thankful for that advice.

I like the emotion and the energy this painting portrays. I can sense the movement and interaction in this family. The parents' focus was in each other, and the chicks begged only from the mother. Of course I am biased.

What I don't like is the rooster looked a little slim to me. I would love to have painted a fuller lower body. I think I painted his foot wrong. Had I painted his toes facing the viewer, it would have suggested a body turning towards the viewer, thus presenting a narrower girth.

The angle of the leg stance did not seem right either. It was too straight. I was so carried away by the thought of standing pound and tall that I ignored the natural stance. Had I superimposed the leg skeletal structure onto my rooster to begin with, in my mind at least, I would have avoided this mistake.

The above illustration shows the relative angles of the femur, tibia and the tarsometatarsals of the rooster's leg. It is obvious that the leg does not go vertically up and down. Just to prove my point I digitally moved the leg to the new position. I think it looks much better this way. What a difference 9 degrees off center makes!

Again, Happy New Year!

Saturday, January 28, 2017

Sunday, January 8, 2017

Same Roots, Different Feel

Now that I have two paintings of banyan tree roots, I'm left with the task of deciding which one I like better.

Now that I have two paintings of banyan tree roots, I'm left with the task of deciding which one I like better.

The one on the right is methodical, deliberate and manicured. The one on the left is devoid of discrete lines and comprised mostly of shadows.

The right one gives a very detailed accounting of where everything is. There seems to be order in the chaos, if one is interested and motivated to find out. The one on the left just stares at you; you either hate it or love it.

Somehow the left one elicits a stronger emotional response from me. I can't really put a finger on it. Perhaps it's my dark personality. In fact as it stands right now, the more I look at the one on the right, the more anemic it seems.

So now I have to choose a piece for an exhibition and I am still vacillating between the two.

In a way I would really hate to lose the one on the right, if by some weird luck I manage to sell the piece. I want to be able to savor the fruit of my labor a bit longer, especially after the enormous amount of time and effort into it. Something tells me that painting is not fully done yet.

The fact that there are leaves depicted in the painting added another layer of symbolism to the work. Chinese has a saying that as the leaves fall, they return to the roots. The meaning could be literal, but it actually describes the cycle of life. Leaves mature, fall, and decompose and return the nutrients to the tree to be recycled. We also have another saying; whenever one drinks water, think of where it came from. So along with finding one's roots, one also appreciates the natural cycle of life.

One might say that the one on the left is a shallower painting, but only I know the hidden meanings. So I will go with my gut feeling, put the darker one into the exhibition, the one that is more superficial yet elicits a stronger feeling.

I also want to show the translucent property of the semi-sized Xuan. Ink from the brushstrokes totally penetrated the paper, such that the back side of the paper showed a painting in reverse.

Here's the back side of the one on the left

and the back side of the one on the right

This is the reason I worked on my process of Suliao Xuan Ban; on the process of mounting on plastic. I wanted the effect of a float that can be viewed from either the front or the back. Perhaps the painted panes on a lit lantern illustrate my point.

The right one gives a very detailed accounting of where everything is. There seems to be order in the chaos, if one is interested and motivated to find out. The one on the left just stares at you; you either hate it or love it.

Somehow the left one elicits a stronger emotional response from me. I can't really put a finger on it. Perhaps it's my dark personality. In fact as it stands right now, the more I look at the one on the right, the more anemic it seems.

So now I have to choose a piece for an exhibition and I am still vacillating between the two.

In a way I would really hate to lose the one on the right, if by some weird luck I manage to sell the piece. I want to be able to savor the fruit of my labor a bit longer, especially after the enormous amount of time and effort into it. Something tells me that painting is not fully done yet.

The fact that there are leaves depicted in the painting added another layer of symbolism to the work. Chinese has a saying that as the leaves fall, they return to the roots. The meaning could be literal, but it actually describes the cycle of life. Leaves mature, fall, and decompose and return the nutrients to the tree to be recycled. We also have another saying; whenever one drinks water, think of where it came from. So along with finding one's roots, one also appreciates the natural cycle of life.

One might say that the one on the left is a shallower painting, but only I know the hidden meanings. So I will go with my gut feeling, put the darker one into the exhibition, the one that is more superficial yet elicits a stronger feeling.

I also want to show the translucent property of the semi-sized Xuan. Ink from the brushstrokes totally penetrated the paper, such that the back side of the paper showed a painting in reverse.

Here's the back side of the one on the left

and the back side of the one on the right

This is the reason I worked on my process of Suliao Xuan Ban; on the process of mounting on plastic. I wanted the effect of a float that can be viewed from either the front or the back. Perhaps the painted panes on a lit lantern illustrate my point.

Wednesday, December 28, 2016

Trials and tribulations

I finally had the banyan roots painting darkened to the point that I considered was dramatic for the piece.

I also emphasized the shadows on the left and the under side of the roots. The effect was as if one was shining a spotlight on them. The whole set up reminded me of those portrait head shots from the studios. To maximize the impact, I would need to hang the painting on the right side of the display area, surreptitiously forcing the viewers to look at it from the left, hopefully amplifying the perspective.

I chose to employ the traditional cinnabar color seal, arguing that this dark piece could use a hint of color, to jazz it up a bit, in a subdued way. I chose the negative seal, thus the script would be the color of the painting. Since the painting was so dark, the script was not immediately legible, inviting the viewers to investigate further to decipher what was being carved. I think this adds to the overall mysterious feel of the painting.

I wanted to continue my experimentation on my Sulio Xuan Ban format, but I wanted to try the wet mount using starch. I began with the back side first, since any mishaps were not going to be catastrophic. I used a blank piece of double Xuan, brushed on a moderately thick layer of starch on the plastic and laid the Xuan on it.

So far so good. I grew a little bolder.

When it came to the top side, the painting side, I used the backing that was already glued on as a placement guide. The semi-sized Xuan was a lot flimsier than the double Xuan and it was difficult to post it correctly. The leading margin softened and wilted immediately when placed on the wet starchy plastic surface and any subsequent yanking or adjusting only made matters worse. I was also running the risk of tearing the Xuan like a piece of wet paper towel.

My heart was in my throat; I was about to encounter my Waterloo.

My dilemma was that if I had attempted to lift the whole piece, the paper might not support the wet weight and would tear for sure. If I left it there, then there were simply too many folds.

I had to find a way to salvage this, and fast. I remembered watching on YouTube how auto body shop technicians would apply protective film to the car body. I remembered them using shampoo to float the piece so the film can be manipulated easier while on the car. Obviously I would not use shampoo, but I grabbed my spray bottle and thoroughly wet the entire painting.

That seemed to work. I could now press against the plastic and apply firm but steady pressure on the Xuan to make it slide on the plastic, gradually eliminating the unwanted folds. I started from one edge and patiently but gingerly moved to the other areas, all the while keeping wetting down the paper.

After what seemed like an eternity, most of the major folds were gone, and the paper was squared up.

Time to put layers of newspaper on top of the wet mess to soak up the excess water, and to protect the painting from the harsh bristles of the palm brush that was used to tamp down the paper onto the plastic.

This insert showed the effect of tamping. The left side, which was tamped, was drier and much smoother, devoid of bubbles.

The entire piece was treated this way, and allowed to dry.

A sigh of relief ! I've averted a cataclysmic blunder.

To my disappointment, I found out that the Xuan did not stick to the plastic as I had anticipated. I could peel off the entire piece as if it was a static cling.

It worked on the back ! My theory was that the profuse wetting during my rescue process severely diluted the starch, to the point that adhesion was greatly diminished. The paper itself was flat and stiff though. Reminded me of the starched school uniform days!

Should I reapply with the thicker starch now?

I decided against it. I didn't want to repeat the same mishap. I couldn't afford to destroy this painting now, not when it was committed to an impending exhibition. My initial eagerness to wet mount this piece was fueled by the success I had with the back piece that was used as a white board. So I dry mounted it.

I shall wait for another opportunity to try my wet mounting on plastic. I'm in no hurry.

I also emphasized the shadows on the left and the under side of the roots. The effect was as if one was shining a spotlight on them. The whole set up reminded me of those portrait head shots from the studios. To maximize the impact, I would need to hang the painting on the right side of the display area, surreptitiously forcing the viewers to look at it from the left, hopefully amplifying the perspective.

I chose to employ the traditional cinnabar color seal, arguing that this dark piece could use a hint of color, to jazz it up a bit, in a subdued way. I chose the negative seal, thus the script would be the color of the painting. Since the painting was so dark, the script was not immediately legible, inviting the viewers to investigate further to decipher what was being carved. I think this adds to the overall mysterious feel of the painting.

I wanted to continue my experimentation on my Sulio Xuan Ban format, but I wanted to try the wet mount using starch. I began with the back side first, since any mishaps were not going to be catastrophic. I used a blank piece of double Xuan, brushed on a moderately thick layer of starch on the plastic and laid the Xuan on it.

So far so good. I grew a little bolder.

When it came to the top side, the painting side, I used the backing that was already glued on as a placement guide. The semi-sized Xuan was a lot flimsier than the double Xuan and it was difficult to post it correctly. The leading margin softened and wilted immediately when placed on the wet starchy plastic surface and any subsequent yanking or adjusting only made matters worse. I was also running the risk of tearing the Xuan like a piece of wet paper towel.

My heart was in my throat; I was about to encounter my Waterloo.

My dilemma was that if I had attempted to lift the whole piece, the paper might not support the wet weight and would tear for sure. If I left it there, then there were simply too many folds.

I had to find a way to salvage this, and fast. I remembered watching on YouTube how auto body shop technicians would apply protective film to the car body. I remembered them using shampoo to float the piece so the film can be manipulated easier while on the car. Obviously I would not use shampoo, but I grabbed my spray bottle and thoroughly wet the entire painting.

That seemed to work. I could now press against the plastic and apply firm but steady pressure on the Xuan to make it slide on the plastic, gradually eliminating the unwanted folds. I started from one edge and patiently but gingerly moved to the other areas, all the while keeping wetting down the paper.

After what seemed like an eternity, most of the major folds were gone, and the paper was squared up.

Time to put layers of newspaper on top of the wet mess to soak up the excess water, and to protect the painting from the harsh bristles of the palm brush that was used to tamp down the paper onto the plastic.

This insert showed the effect of tamping. The left side, which was tamped, was drier and much smoother, devoid of bubbles.

The entire piece was treated this way, and allowed to dry.

A sigh of relief ! I've averted a cataclysmic blunder.

To my disappointment, I found out that the Xuan did not stick to the plastic as I had anticipated. I could peel off the entire piece as if it was a static cling.

Should I reapply with the thicker starch now?

I decided against it. I didn't want to repeat the same mishap. I couldn't afford to destroy this painting now, not when it was committed to an impending exhibition. My initial eagerness to wet mount this piece was fueled by the success I had with the back piece that was used as a white board. So I dry mounted it.

I shall wait for another opportunity to try my wet mounting on plastic. I'm in no hurry.

Thursday, December 22, 2016

Finding My Roots, Chapter Three

I wanted to leave the lower left corner devoid of details, to contrast with the upper right corner of intricate arrangements of roots. Call me fastidious but somehow I always bear in mind the importance of contrast in my painting, the ying and the yang, and in Chinese terms, the host and the guest. Perhaps this is even more critical in a painting like this, where the entire paper surface seemed to be occupied by the same monotonous subject matter. Soon I deemed that corner to be too meager, so I turned to my leaves and gravels.

Judicious application of shadows around the edges gave them a three dimensional feel, lifting them off the ground. The shadow of the top leaf gave the illusion that it was folding onto itself.

I happened to notice that when viewed from a very shallow angle, the surface of the paper is buckled with lots of tiny undulations, as a result of all the brushstrokes. That explains why the ink wash sometimes found interesting routes on its own. By capitalizing this phenomenon I was able to form more natural margins on my roots. At the very least, I could use that as a guide to apply my shadows. This is an advantage this semi-sized Xuan offered.

There were lots of places where roots branched out like a cross, and shading was done by sitting the belly of my brush at these axillary points. This is analogous to running a round file at the inside corner of crossbars to get a nice chamfer edge.

My finished work:

I particularly like the upper right quadrant of the painting. It narrated very nicely the relationship of the mangled roots; which ones were on top, which ones were on the bottom. I could almost trace each root as they emerged from the main branch and then fused with others or submerged into the soil. This is what we Chinese meant when we choose to say "to read a painting" over "to view a painting". By reading a painting, one is not turning over pages, but all the elements and nuances with our mind.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)