I was asked to do a Chinese Brush painting demonstration at one of the local venues. I told them I would, and my topic would be landscape paintings.

Landscape painting is among the most difficult genre to master. Needless to say it requires expert brush skill, but it is often laden with so many rules and doctrines, to the extent that it smothers creativity. Chinese landscape paintings are in essence impressionistic abstract paintings that portray a a state of mind, a philosophy, rather than an object. It is this ether that gets lost in the process. I suppose one could describe a well manicured garden with all its physical attributes, design elevations and its eclectic collection of flora but it is the enjoyment of the garden, be it rests merely on the surroundings, or otherwise the sentiments it evokes, that ultimately establishes the garden.

I am certainly no expert in this area, and that is exactly why I wanted to take up this self imposed challenge. I wanted to approach this demonstration from the standpoint of a student.

A student must do homework, and I need to have a clear road map in my mind as to what I plan to present, so I settled down to devise my program. My experience with these demonstration sessions are that they are always fluid. Some audience members are surprisingly well versed, whilst others are totally uninformed and I need to be able to talk at both levels at the same time. We could be examining one topic and it quickly digressed to something else. That is the reason I need to be more than a one trick pony and have an arsenal of useful skills and information that I can retrieve from.

Students of classical Chinese Brush are aware of the two main styles of painting, namely the

Gonbi and the

Xieyi; where the former is a more formal style with distinct outlines and filled in color and the latter is more expressive brushstroke ( especially broad side-tipped used to describe surfaces) format. Landscape paintings demand a good understanding of the

Ji Ben Gong ( fundamentals ) which deals with

Gou, Chuen, Ts'a, R'an and

D'ian ( outline, texture, rub, wash, dot )

Landscape paintings are often a combination of the two, although there are works that are predominately one or the other. I shall start with the study of the more brushstroke-weighted ( surface weighted) one. Here the brushstrokes represent a shape, a landmass in this case; and also the light values and shading.

I reached into my tools bag and dug up an old model that I fashioned with foam core board

using charcoal I rubbed the contour onto my

Xuan ( I must emphasize that this is

not the traditional way of doing Chinese landscape paintings, but strictly something I devised to help myself and others understand the brushstrokes)

I started on the left side and built my backdrop of a trail with steps using light and medium ink

Using dark ink, I sought out the areas that are shielded from the light and did my side tip brushstrokes

As the ink is depleted gradually from the brush, take advantage of that by laying into areas that require a lighter value. A clear understanding and concept of how the rocks are presented helps to write in these brushstrokes. In an ideal situation, the charcoal contour lines should not be visible at all, since they never existed to begin with. They are only "cheat lines" to help the student visualize the structure. Thus I was trying hard to conceal these lines.

Moving on to the right side, I inserted the rest of the backdrop

Voila, the completed sketch

Before I proceed to my next etude, let me just say that I am not too happy with the above rendition.

The more brushstroke-weighted (surface-weighted) style is supposed to be more spirited and free and yet I don't see that at all. I believe the culprit is in my charcoal sketch lines. Those were supposed to guide me as to where to write in my brushstrokes but they ended up being quite restrictive. I was trying to conceal them as well as follow them and thus my brushstrokes looked more like tracings than actual strokes. They lacked gusto!

While my scheme MIGHT help us understand where to wet the paper with ink, it also created a rather rigid image.

I turned my attentions to the more traditional method of painting landscape, half

Gonbi, half

Xieyi.

This process begins by establishing outlines of hills, rocks, trees etc., anything that is in the foreground or middle-ground. These areas enjoy a more rigorous and detailed description from the brushstrokes. Thus the process of

Gou is the first step.

As the ink gets depleted from the brush, which also gets drier as the writing continues, we need to strategically start writing in areas that demand a lighter tone, also the process of

Chuen and

T'sa as the opportunities present. In other words,

Gou started out as a single minded procedure, but as the brush changes its characteristics then we take advantage of the situation by incorporating

Chuen and

T'sa. This concurrent administering of the 3 techniques gives the painting a more cohesive feel.

The background, or objects far far away are always depicted with the broad strokes without

Gou lines. These are suggestions that something exists out there. The broad side-tipped strokes are used.

After the basic skeleton is acquired, it is time to employ

R'an, to add shading and establish the darker tones.

R'an can be most effective and dramatic when corroborated with the

Chuen that is already in place. It really defines the faces of the rocks and the texture. It helps if we can hypothesize and visualize where and how the light illuminates the formations.

Using burnt sienna, or tea, we judiciously color in the highlighted areas

Write in the darker areas with indigo and ink mixed. Do this before the tea or burnt sienna dries so the transition of color is smooth and is easier on the eyes. Also use a non transparent color like green label one to write in the flat land and shore at the base of the conical pillars.

Close-up of fine tuning the rock face

The reason for using a non transparent color of the shores is so that when we put in the reflection of the pillars in water, the gouache like color is not covered, retaining the integrity of the shores.

D'ian is selectively applied to hide bad lines, or to accentuate a contour line, suggesting vegetation in the crevasses, tree stands, blades of grass along the shoreline or simply as decoratios to take up space, like a potted plant in the corner of a room. Obviously tree leaves are prime candidates for its application.

The brushstrokes need to be lively and expressive, despite the fact that they seem like mere dots.

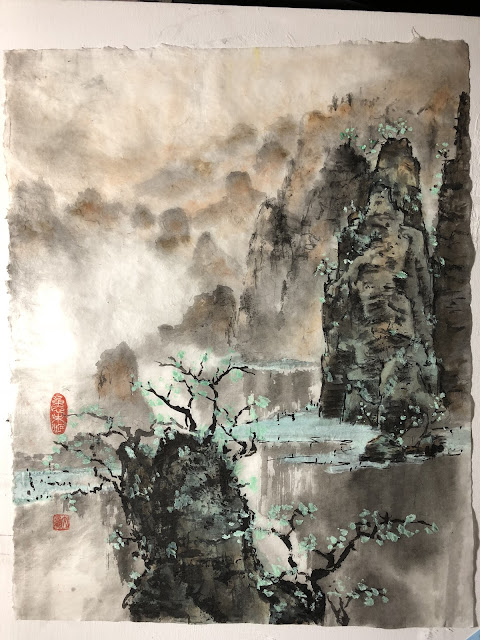

The finished painting

which is loosely based on this scene from Guiln

I feel a lot better now.

I feel like I have given the impending demo an honest preparation.

I feel like I have gone to the confession booth and have all my sins absolved.......