With Covid still unabated I needed to find something to do. Something useful, something stimulating to do.

I saw the pile of old vinyl LP records leaning haphazardly on my bowing plank shelves and decided that perhaps I could digitize them so that I could have them in my music library and stream them at my leisure. My records are 20 to 50 years old. I still have a few that were my dad's. I have my nice "audiophile" turntable and my computer has the Audacity program installed. Should be a walk in the park.

I eagerly cleaned off the dust collecting on the lid of my record changer. Hooked up the RCA outs from the turntable to a 3.5mm stereo adapter and plugged into the headphone jack of my computer.

I acknowledged to my computer that I was plugging a line input; not a microphone; not a headset. I then opened the lid to my turntable and pressed "On".

Nothing happened.

My turntable is from the 90's. At the time it could be considered a nice turntable and had the touch sensitive capacitance buttons for changing play speed. I so loved this piece of machinery. It was so futuristic. It has not been powered up for at least 20 years.

So I had a failed power switch. Removing the bottom of the turntable confirmed my diagnosis. The plastic casing of the switch succumbed to the pressure from the spring inside. I fired off an order to procure a new power switch that would fit my machine.

The new switch came. I installed it. Powered my turntable on and the capacitance buttons lit up. I was almost like a new parent.

I pressed the "33" play button and it flickered for a bit and jumped to the Stop button; all by itself. So this happy new parent grew very concerned. My new baby was not healthy.

A quick research online revealed that my vintage turntable was prone to capacitor failure and described some of the problems I was witnessing. I had tinkered with soldering and building my vacuum tube radio when I was a teenage so I decided that replacing a few capacitors was not beyond my abilities.

One of the casualty of Covid was that a huge chain store which sells electronic parts for hobbyist closed its door for good. I had no choice but to buy parts online. I couldn't buy just one. Capacitors came in strips of 5 or 10. I suppose that was the price to pay for wanting to relive the past.

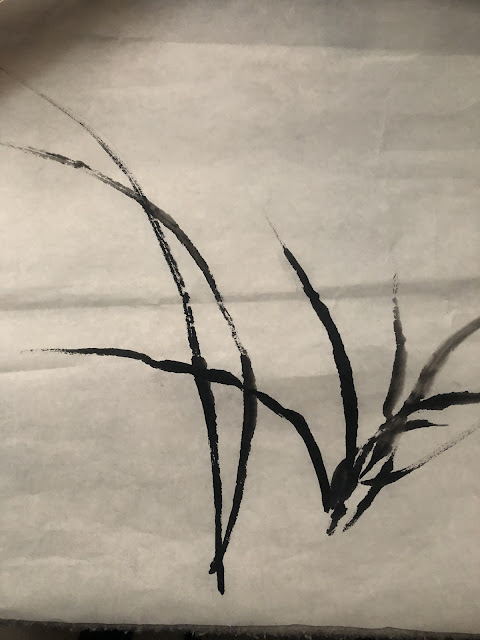

While waiting for my parts to arrive I decided to practice my Ji Ben Gong ( basic skills ) by painting orchids. Orchid paintings are favorite subjects for Chinese brush painting and they require exquisite brushstrokes to emanate the beauty and the reclusiveness of the plant. Strictly speaking the so called "painting" is actually a collection of calligraphy writings, and these calligraphic brushstrokes bestow the abstract and impressionistic qualities of such paintings.

My training in orchid painting, like most of my Chinese brush trainings, is by rote learning. Almost all my teachers demanded repeated studying and emulations of known paintings, and rehearsing the necessary brushstrokes to acquire the skill of orchid painting; all in the name of developing Ji Ben Gong. Obviously the downside of this practice is that all orchid paintings look alike, since the same brushstrokes and compositions were practiced incessantly, not only by me, but by all serious students.

Since I haven't painted an orchid for a long time, I decided to start by doodling and trying to recall my muscle memory of orchid painting.

I constantly looked at my tracking page from the vendors, as if this would hasten up the delivery of my needed parts. I was being a kid again.

The day came when the brown delivery truck pulled up next to my door. I ripped the capacitors from the packaged strip array of 5's, almost with the same fervor as trying to open up a package of prophylactic for the very first time, and impatiently waited for my soldering iron to heat up; fidgeting with the new capacitors to determine which lead was negative, so that I would not reverse polarity when inserting my new capacitors.

I replaced two capacitors on the circuit board, put the screws back in and fired up my turntable.

Success! My newborn had been cured. I was a jovial new parent again. Now I could use my vintage equipment to relive my past again. In Da Gadda Da Vida, White Rabbit...........

Working with Audacity and iTunes was such fun. My digitized music library was growing slowly and the past was definitely worth reliving. I streamed part of the collection to my sound system, and it sounded awesome, the fact that I could no longer hear beyond 10 kilohertz notwithstanding.

It was all in my head. There was no better way to endure the pandemic by doing what I was doing. Useful, stimulating.

Orchid painting can wait. After all I was just trying to brush up my basic skills in painting by revisiting the past. It really wasn't tops in my agenda.

Then one day the STOP button light on my turntable would not come on. I thought my deck was unplugged. The lights worked on the 33 and 45 buttons.

Must be a burned out lightbulb. How difficult could it be to replace the lightbulbs.

Off came the bottom of the turntable. I located the tiny lightbulbs underneath the capacitance buttons and switched out the bulb for 45 with the STOP, since I don't play 45's. Put everything back and to my chagrin the turntable was saddled with erratic speed switching on its own.

Further research revealed that the circuit used the resistance of the lightbulbs in its capacitance calculations. The tiny current draw by placing one's finger on these capacitance buttons was tied in to the lightbulbs and therefore this was a scenario where not just any lightbulb would work. A set of 3 lightbulbs for this particular turntable would cost me $21 to buy. Should I just buy them and possibly exorcise my erratic speed demon?

I wasn't so sure at this point. I looked at the schematic and it showed the correct voltage at different points of the wiring schematic. I figured with a little patience I could retrace the different paths of the schematic and with the 6 different potentiometers on the circuit board surely I could adjust the voltage to spec without replacing the burnt lightbulb and my vintage machine would work again. Besides this could offer me a new experiences to tinker or experiment with something. Just like painting, I told myself.

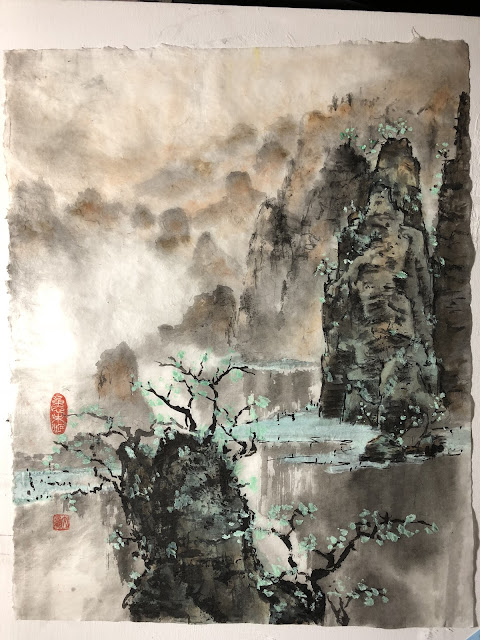

In the spirit of toying and experimentation, with the same aplomb applied to trying to fix my old equipment, I tried painting on a matte photo paper. Curious to see what it was like.

The result was not ideal. The photo paper called me out by amplifying my indecisiveness in my brushstrokes. They seemed a little pretentious and not spontaneous enough, especially with regards to the petals of the orchid.

In the days and weeks that ensued I realized that I was in over my head with fixing my turntable. I did not have a basic understanding of the schematic or how the circuit was designed and I based my optimism on the assumption that I could somehow adjust the voltage to spec. With 6 different potentiometers and a burnt out lightbulb that I kept turning and switching around I had totally lost track of what I had touched and altered. I was lost in a deep canyon with no identifiable landmarks.

Back to the drawing board, literally.

I started out with the leaves of the orchid plant. As I had mentioned before in my blogs about traditions, I was mindful to keep the phoenix eye in the basic construct of the leaf arrangement.

Although the so called host and slave leaves were not well defined, the nuance of such a relationship still governed the composition in this complex arrangement. Is this the only way to portray orchid? I would hope not; but old habits are hard to break, especially for students of rote learning. This type of presentation nonetheless provide a comfortable space, for both the viewer, and the painter.

So the pandemic is not relenting and my vintage record player suffered a fatal blow from my malpractice. In retrospect the viral pandemic offered me more leisure time to do something that I normally wouldn't have done, and my desire to relive or to preserve the past led to my attempt to convert analog tracks to digital bits. I see a parallel in my naïve determination to tackle something that I only had a superficial knowledge of and my painting by rote. In electronics repair I thought I could follow the schematic and somehow attain the correct voltage without knowing what led to the deviation to begin with. In painting by rote, I followed the traditions without clearly understanding what dictated that practice. My saving grace is that sometimes I have more gall than brain and sometimes good things happen. The truth is that my painting attempts could be serendipitous but luck is more stingy when dealing with technical issues. One has to have Ji Beng Gong, or the basics, by hook or by crook.

How else could I be vacillating between euphoria and despair, but by sucked in by the romantic notion, that I could hold on to things in the past and relive them. However, on this date, I bid adieu to my vintage turntable, a small but significant part of my past.