I was nervously fidgeting with objects on the coffee table as my mind was racing, trying to find a polite and meaningful conversation. I am just not adapt at social gathering with people that I barely know. More often than not, I was afraid to be too opinionated, once engaged in an exchange. Surprise!

Then my sight latched onto this teapot.

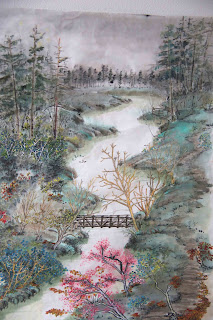

I've always maintained that Bi-fa is the quintessential element in defining Chinese painting. Here is a simple drawing of a dwelling on water. None of the associations in this scene made any sense. In fact it bordered on being absurd. Nonetheless we know immediately this is a Chinese painting.

Was it because it has Chinese thematic objects? Probably. It was the Bi-fa, however, that I consider to be the calling card in this instance; albeit the work was not done with a brush but with a carving utensil.

The scratch marks detail clearly the starting points, progressing to lines with various pressure and width. This is really no different from drawings made with pencils or charcoal sticks. The pressure and speed and decisiveness of the strokes are clearly documented. Thus the tracks made were not wet noodles, but lines with Li (strength, energy). Bi-fa is used generically in this instance.

The layout itself follows the traditional landscape doctrine, subscribing to the Three Perspective practice, height, level and depth.

Trees were depicted in the traditional abstract fashion. Hemp chuen was applied to boulders in the fore front and hills in the right background, whereas the rock pillars on the left received the Axe chuen. These are all classical methods used to describe texture and topography.

So even with clay, and without using a brush, the artisan still followed the tradition and demonstrated the traits of a Chinese painting.