I grew up in the era when composition class required the use of writing with a Chinese brush and ink. The brush might as well be a piece of twig for me. Something that I could leave a legible mark on my exercise book so that my teacher could read and grade my work. In those formative days, I was not fortunate enough to receive the mentorship of how to properly use a brush. Sure the teachers showed the different roots of the Chinese character and there were Fa Tie ( books of model letter, model character) for us to copy during penmanship classes, but we did not receive individual guidance. Perhaps the class size was too big.

A brand new Chinese brush has its hair glued together to form a point and is rather stiff. The new brush is meant to be soaked in water to dissolve the glue such that the hair is separated to its individual strands. The scattered and spread out hairs would come back to a point after wetting with water or ink; when surface tension works its wonders.

The new brush is on the left and a used brush is in the middle. The brush on the right shows how the hairs would come back to a point when wet.

Imagine having a wet wad of hair at the end of a thin stick and I was suppose to wield that and write thin lines with that floppy mess? No way!

My answer to that was to not soak the new brush in water. I would just jam the tip of the new brush onto the desk, such that the first few millimeters of hair separates, and I would write with that very limited "point". Obviously that negated all the virtues bestowed by a Chinese round brush. My lines were all thin and even. Neat!

As the act of writing continued, the bristles of the brush became more scattered. Ink and water had crept up to the belly part of the brush and was dissolving the glue. The writing process became more labored. I became more frustrated. My lines were getting fatter and irregular. Fortunately I never washed my brush after each writing. The ink would dry on the brush and it became stiff again.

I wonder how many of us have the same story to tell.

I might as well be using a ballpoint pen, but this was before ballpoint pens were invented. Yes, I'm that old!

It wasn't until I was in secondary school when Chinese Brush painting was part of the curriculum that I realized the wonders of the Chinese brush. I basically had to re-learn everything about the brush. All that became more succinct when I started to learn brush calligraphy in earnest. It became clear to me why people say that calligraphy is the foundation of brush painting. It's all about the brush, and the brush is more than a mark making instrument.

In calligraphy class, we were told to pay attention to the tip of the brush. As the brush traverses the paper to write a line, the tip could be placed at the center of the line, hence the center-tip brushstroke. The brush tip is in line with the direction of travel of the brush. If the tip however is pointing at any angle other than the direction of the travel, then the nab of the brush is basically dragging along and not in the orientation of the travel and that describes the side-tip brushstroke.

To illustrate the cumbersome statements above, I am write two lines with a brush that has the dark ink on the tip of the brush only. Obviously the ink is going to migrate to the sides and belly of the brush, but the brush tip should leave the darkest mark on paper.

Hence the top line is done with the center-tip brushstroke. Dark ink is at the center at the start of the brushstroke and gets fainter as the brush travels. The center white line is actually the mark left by the tip of the brush as the ink on the tip depletes and only water remains. This brings up the special quality of the Xuan paper we use for our paintings. It registers everything from our brushstroke.

The line on the bottom shows ink at the start, but loaded to the top and continues to load up on the top margin of the line. This is due to the position of the brush tip, which is pointed towards the top of the paper as the brush is dragged to the right. In essence the brush tip is at a 90 degree angle to the line of travel. Again the void space in the brushstroke represents the part of the brush where ink is depleted.

Certain fonts in Chinese calligraphy mandates the use of strict center-tip brushstrokes, whereas others require both center-tip and side-tip brushstrokes. The accomplishment and hubris ( or lack of ) a calligrapher depends on the correct application of the brushstrokes. When one looks at a piece of Chinese calligraphy, each brushstroke encompasses different widths, shapes, bends and corners. and yet they are all discrete brushstrokes. A stick or twig certainly can't do that. They would have to go back and fill in to modify the shape of the markings.

When we say "we write a painting", we mean exactly that. We use center-tip and side-tip brushstrokes to achieve the shapes and lines of objects. A prime example would be paintings of bamboo.

Bamboo leaves are nothing but lines. The entire shape of the bamboo leave, or stem, is done by discrete brushstrokes and not by filling in the space as one would normally associate with painting. Again, using my "tip-loaded-only" brush, I have "written" the following "painting",

The 3 bamboo leaves on the left are center-tip brushstrokes and the one on the right is side-tip. An easy way to tell is by look for the points at the start of the brushstroke. If the point is in the middle, it is likely center-tip. If the point in at a corner, then the brushstroke is side-tip.

In the example above, C denotes center-tip brushstroke, and S is for side-tip brushstrokes. The arrows point to the line (edge) left by the tip of the ink-loaded brush tip. One can see the point at the start of the brushstroke is at the corner, and the brushstroke has ink loaded on one side only.

A painting often requires both kinds of brushstrokes to make it interesting and harmonious.

The following is a pointing of bamboo leaves done mostly with center-tip brushstrokes

Here is an example of one done mostly with side-tip brushstrokes (you can see the start of the brushstroke is a flat end, feels like putty knife)

Hopefully you can feel the different nuances presented by the two examples above. Generally speaking, in paintings anyways, center-tip brushstrokes can be so "proper" that they become dry and monotonous. Side-tip brushstrokes are more rambunctious and spirited, but can get away from you really easily.

Speaking of being rambunctious, here is an example of just one bamboo leaf, done in the side-tip brushstroke:

The painting is the work of the famous Ling-nan style Master Chao Shao-An.

Which one do you prefer? Do you paint (write) with those distinctions in mind?

Using the side-tip brushstroke, I "wrote" two half-circles. I loaded the brush tip only with ink to better show the track of the tip.

I then garnished my half circles with some lines and now we have an insect.

These are all discrete brushstrokes but I am making a case of the character of the brushstrokes. The legs on the left side of the insect were done center-tip. The ones on the right were done in side-tip brushstroke, where I could modulate the shape of the line with greater ease. Perhaps this is not too evident due to the small size of the brushstroke, but hopefully one can at least surmise that the legs on the right are more interesting and life-like.

Here's another example of how simple written lines and appropriate brushstrokes can represent an insect in this case. This is what "writing" a painting means.

When we mix center-tip and side-tip brushstrokes, we can transform simple lines in a fish. I am hoping that one could easily tell that the pectoral fins are definitely side-tip brushstrokes.

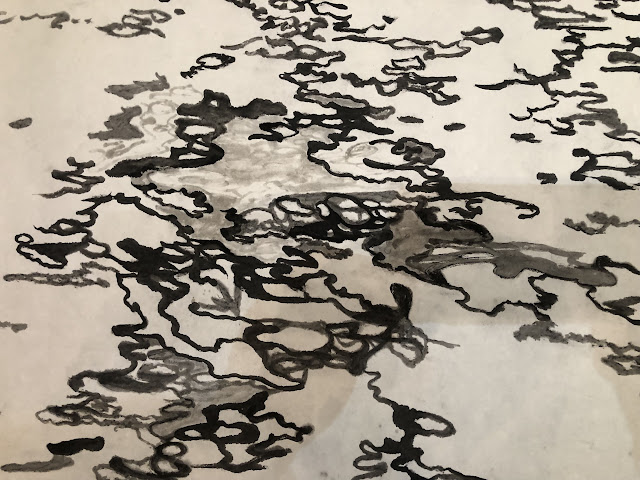

Just for fun, I am including the following photo is see if one can distinguish the two different brushstrokes

In painting, we would use the entire nap of the brush. We use the tip, the side and the belly. We hold the brush vertical, leaning, or even rolling flat. I suppose the side-tip brushstroke is more exaggerated and expansive in brush painting.

Again using a tip-loaded brush with ink, side-tip brushstrokes describe the petals of a flower.

When the brush is totally flat on the paper, the with judicious positioning of the ink-loaded tip, we can see how a variegated petal or leaf can be described.

I hope to plead my case that the Chinese round brush is not just a tool for mark making, or dabbing. The proper use of the brush demands knowledge, and most of all, practice. If we fail to see it as a calligraphy instrument first, then we have minimized its importance in the realm of Chinese paintings.