A friend showed me a painting on silk and it looked very nice. Except that I didn't think the material was silk.

Many of my friends do the Gongbi style of Chinese brush and they typically paint on silk. They buy their yards of silk from art supply stores found on the Internet. To me that material looks like a very fine mesh translucent screen and it feels stiff and brittle, more like nylon than silk. It also tears rather easily. I just can't believe that this is the revered silk that is used to weave clothes.

I could recall seeing antique silk paintings in museums and I would very much try to re-create that ambience. My plan was to get some silk fabric and use that as my canvas.

I had some scraps of a brownish silk fabric at my disposal so I cut out a swatch and stapled that on a regular canvas. I was lazy.

The fabric looked a little too red for me, so I thought I could tone it down a bit by using a light green wash. Except that the silk fabric would not take on the wash, as if it was treated with Scotchgard. The wash was beading up on me.

I figured I needed to condition the fabric first, so I mixed some alum solution with my wash and tried again. Perhaps the alum in my wash could work as a mordant and make the color stick. Maybe?

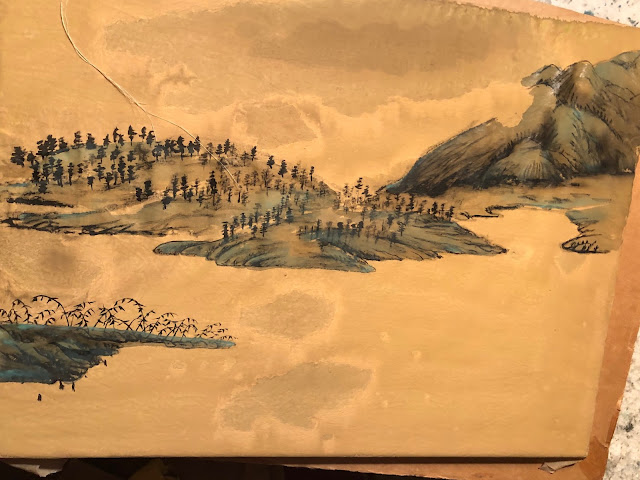

I didn't know whether it was the alum or was it my perseverance, the silk fabric was taking on the wash nicely now. Unfortunately the fabric didn't present nicely at all after the wash dried up. Somehow the surface was very blotchy. Perhaps my alum solution was not mixed in evenly with my light green wash so there was uneven distribution of the pigments. Now I was faced with painting something that could side-step or blend in with the discolorations. The painting I recalled seeing in a museum had a very simple composition. A spit in the middle of the river, with the mainland as the background, dotted with trees. I remember vividly that it was the dotted trees that helped to define the topography of the land. Sort of like the traditional moss dots, but transforming them into trees. I could borrow the discolored blotches as the typical clouds and mists one sees in traditional Chinese landscape paintings. How clever!

The soiled spots in the front center were too ostentatious. I needed to tone them done. I tried to hide them with a darker shade of green, suggesting a body of water, with uneven surfaces caressed by the wind.

Distant mountains occupy the background, as I recalled.

The cloud/mist feature was perfectly represented by the swath of void.

Simple hemp fiber chuen depicted the landmass in the background, nothing complicated.

After I had all the features down on the painting, I painted in a few punts. The ones in the channel would get a white sail, adding an exclamation mark.

I wouldn't say this was an exercise in futility, but it was certainly frustrating; especially in the beginning. I was constantly needing to find ways to amend my boo-boos but in the end I felt satisfied and enjoyed the journey. I suppose that's the reason I paint.

I am an enthusiast of Chinese Brush Painting and I would like to share my trials and tribulations in learning the craft. I want to document the process, the inspiration and the weird ideas behind my projects and to address some of the nuances related to this dicipline. I hope to create a dialogue and stir up some interest in the art of painting with a Chinese brush on Xuan. In any case, it would be interesting to see my own evolution as time progresses. This is my journal

Monday, June 17, 2019

Friday, May 31, 2019

Epilogue to Yellow Mountain

I looked at my finished Yellow Mountain painting and I felt something was amiss. I did not get the fulfillment I was expecting. It took me a little while to put a finger on what was happening.

I did not create enough separation between the mountain features to effuse the grandeur and vastness of this landscape.

Upon re-examination of my work, the impression was that this was a bird's-eye view of a mountain range. I could have and should have widened the perspective of the features. I should have utilized my 18 mm lens and picked a different vantage point to capture the true ambience. Obviously this was not photography and it was too late to do anything.

Or was it?

To prove my theory, I begged the help of technology, Photoshop.

I digitally separated my painting into 3 distinct areas. The foreground on the left, middle-ground would be the 4 peaks of the mountain and the trailing features painted with splash ink brushstroke would be the background. Cloud and mist features would be an effective means for the separation. They are voids that would not appear as omissions.

Immediately I felt the painting opened up and now inviting me to be immersed as a participant.

Since I could not push back the features in what should have been my middle-ground, I experimented with another trick. I wanted to add some incidentals in front of the 4 peaks, thus effectively adding distance.

So birds were deployed.

I had to change the birds from black to white in front of the peaks to make them more conspicuous. Call that creative freedom if one must.

Did this help the painting?

I did not create enough separation between the mountain features to effuse the grandeur and vastness of this landscape.

Upon re-examination of my work, the impression was that this was a bird's-eye view of a mountain range. I could have and should have widened the perspective of the features. I should have utilized my 18 mm lens and picked a different vantage point to capture the true ambience. Obviously this was not photography and it was too late to do anything.

Or was it?

To prove my theory, I begged the help of technology, Photoshop.

I digitally separated my painting into 3 distinct areas. The foreground on the left, middle-ground would be the 4 peaks of the mountain and the trailing features painted with splash ink brushstroke would be the background. Cloud and mist features would be an effective means for the separation. They are voids that would not appear as omissions.

Immediately I felt the painting opened up and now inviting me to be immersed as a participant.

Since I could not push back the features in what should have been my middle-ground, I experimented with another trick. I wanted to add some incidentals in front of the 4 peaks, thus effectively adding distance.

So birds were deployed.

I had to change the birds from black to white in front of the peaks to make them more conspicuous. Call that creative freedom if one must.

Did this help the painting?

Thursday, May 23, 2019

Yellow Mountain

Using my black and white sketch of Huangshan as a reference, I proceeded to paint a larger painting in color. This painting shall have a pronounced yellow tone. You might say that is the personality of this piece.

I loaded the right side of the painting with features and the left side relatively scant as a contrast.

The foreground would be allocated with more detailed brushstrokes, fading to the right and to the back. This initial stage consisted mainly of the Gou and R'an (scribe and wash) portions of the Gou Chuen Ts'a R'an D'ian ( scribe, texture, rub, wash, dot ) process.

The mountains in the foreground is extended to the right and back, forming a S-shaped pattern. This is to satisfy the prescribed requisite of "level perspective" in the traditional sense of Chinese landscape painting.

Adding a light wash to the features allowed me to get a better perspective of what I was doing, especially when the paper was wet

After the wash had dried, I did my Chuen and T'sa (texture and rubbing) brushstrokes. The painting began to take on a more realistic appearance due to the added information.

With the help of selective R'an (wash) brushstrokes, I was able to better reveal the 3-dimensional quality of the painting by depicting the different light values.

A close-up of the Gou, Chuen, T'sa, R'an process. Notice the lack of D'ian (dotting) at this stage. I typically would reserve that for the purpose of concealing bad lines and to add amorphous features to garnish the landscape.

The void expanse was tweaked with clouds and mist, basically a wet on wet technique to borrow from the watercolor vernacular. The effects were exaggerated when wet.

I had a better sense of what the stage looked like after the cloud and mist dried. I began adding more detailed incidental features to the landscape.

This also involved the use of the D'ian brushstroke to ameliorate deficiencies in the painting; to smooth out transitions from one value to another

Here is an example of how all the different brushstroke techniques worked together to form a cohesive feature, evolving from a purely two-dimensional drawing.

Time to stand back and give the painting a rest. The wet paper made the painting very vivid.

I loaded the right side of the painting with features and the left side relatively scant as a contrast.

The foreground would be allocated with more detailed brushstrokes, fading to the right and to the back. This initial stage consisted mainly of the Gou and R'an (scribe and wash) portions of the Gou Chuen Ts'a R'an D'ian ( scribe, texture, rub, wash, dot ) process.

The mountains in the foreground is extended to the right and back, forming a S-shaped pattern. This is to satisfy the prescribed requisite of "level perspective" in the traditional sense of Chinese landscape painting.

Adding a light wash to the features allowed me to get a better perspective of what I was doing, especially when the paper was wet

After the wash had dried, I did my Chuen and T'sa (texture and rubbing) brushstrokes. The painting began to take on a more realistic appearance due to the added information.

With the help of selective R'an (wash) brushstrokes, I was able to better reveal the 3-dimensional quality of the painting by depicting the different light values.

A close-up of the Gou, Chuen, T'sa, R'an process. Notice the lack of D'ian (dotting) at this stage. I typically would reserve that for the purpose of concealing bad lines and to add amorphous features to garnish the landscape.

The void expanse was tweaked with clouds and mist, basically a wet on wet technique to borrow from the watercolor vernacular. The effects were exaggerated when wet.

I had a better sense of what the stage looked like after the cloud and mist dried. I began adding more detailed incidental features to the landscape.

There was prodigious use of D'ian (dotting) brushstroke in this painting. This technique helped to conceal a lot of inadequacies in my brushstrokes and created a pleasant nuance. If you looked closely and compared the before-and-after pictures of the same areas you would notice a lot of the tentative brushstrokes were well hidden now. Perhaps this was pointillism in its infancy. Wink, wink.

Here is an example of how all the different brushstroke techniques worked together to form a cohesive feature, evolving from a purely two-dimensional drawing.

Time to stand back and give the painting a rest. The wet paper made the painting very vivid.

Thursday, April 18, 2019

Three Variations On The Yang Pass

Music and poetry are intertwined with Chinese Brushing paintings in the sense that they often inspire each other. Scholars in the past were expected to excel in painting, writing poetry and calligraphy. It was not uncommon then, for the artist to write a painting with strategic void spaces and garnish that with verses of calligraphy. When I was studying Chinese painting, one of the routine was to paint something according to a poem.

Three Variations On The Yang Pass is a musical piece that is rich with history. This iconic piece has been adapted for different musical instruments and instrumentation, both eastern and western and even choral adaptations.

The musical piece was borrowed from a poem by Wang Wei, a Tang dynasty poet. The poem was incorporated into music, and subsequently amended with lyrics and 3 refrains, thus the three variations. The poem is about Wang Wei seeing a friend off, and Yang Pass is a strategic stop for this intrepid journey. The Pass was a military installation in the old days, and a sentry post on the southern branch of Silk Road.

Wang's friend was assigned to a outpost that is far from the heartlands of China. The location of that outpost would have been today's Kuqa county in Xinjiang, China. Wang supposedly said goodbye to his friend at what would be today's Xi'an. I looked up Google map and the journey from Xi'an to Kuqa is a 36 days trek on foot crossing an arid landscape; nothing to sneeze at.

The following is the Google map showing the points of interest:

White dot is the starting point, Xianyang (Xi'an)

B is Yang Pass

A is the final destination, the outpost at Kuqa

I shall attempt to translate the poem that Wang wrote for the occasion of saying goodbye to his buddy:

The city was shrouded in a light sprinkle, settling the dust on the road

Willows by the inn sprouting green color

Bottoms up, let's finish yet another drink

Beyond Yang Pass there shall be no old acquaintance to be found

It is customary for Chinese to host a farewell dinner and a welcome home dinner for the traveller. The welcome home affair is aptly named "Dust Cleansing Dinner". In other words, retiring the grime and obstacles of the journey taken. In this poem Wang cleverly borrowed the dust theme to pave way for his friend. He was proclaming even the sky opened up with a gentle shower to settle the dust, meaning there would be nothing to hinder a smooth voyage. A good omen.

The word inn painted a picture of travel, and willow is a homonym with the Chinese word "stay". When Chinese present a willow twig as a token for the traveller, it is an expression of not wanting to part company and hoping the traveller would stay a while longer.

Thus the first two verses of the poem seemed to have depicted rain and inn and willow but Wang was actually setting the stage using metaphors. He was supplying the prerequisite of the emotional content, priming our lachrymal ducts for what's to follow.

So let us say bottoms up to yet another drink, and how many drinks have we had? This is your last drink for a while, buddy, because soon you'll have no one to drink with. That's gut-wrenching!

Such is the desolate destitute, please, won't you stay for me? Don't go!

Wang ached.

Parting is such sweet sorrow is a line from Romeo and Juliet, expressing the affection between a man and a woman. In Wang's poem, there is resigned sadness, for a closeness soon to be beyond reach.

That was my inspiration for my paintings

The two versions side by side

Three Variations On The Yang Pass is a musical piece that is rich with history. This iconic piece has been adapted for different musical instruments and instrumentation, both eastern and western and even choral adaptations.

The musical piece was borrowed from a poem by Wang Wei, a Tang dynasty poet. The poem was incorporated into music, and subsequently amended with lyrics and 3 refrains, thus the three variations. The poem is about Wang Wei seeing a friend off, and Yang Pass is a strategic stop for this intrepid journey. The Pass was a military installation in the old days, and a sentry post on the southern branch of Silk Road.

Wang's friend was assigned to a outpost that is far from the heartlands of China. The location of that outpost would have been today's Kuqa county in Xinjiang, China. Wang supposedly said goodbye to his friend at what would be today's Xi'an. I looked up Google map and the journey from Xi'an to Kuqa is a 36 days trek on foot crossing an arid landscape; nothing to sneeze at.

The following is the Google map showing the points of interest:

White dot is the starting point, Xianyang (Xi'an)

B is Yang Pass

A is the final destination, the outpost at Kuqa

I shall attempt to translate the poem that Wang wrote for the occasion of saying goodbye to his buddy:

The city was shrouded in a light sprinkle, settling the dust on the road

Willows by the inn sprouting green color

Bottoms up, let's finish yet another drink

Beyond Yang Pass there shall be no old acquaintance to be found

It is customary for Chinese to host a farewell dinner and a welcome home dinner for the traveller. The welcome home affair is aptly named "Dust Cleansing Dinner". In other words, retiring the grime and obstacles of the journey taken. In this poem Wang cleverly borrowed the dust theme to pave way for his friend. He was proclaming even the sky opened up with a gentle shower to settle the dust, meaning there would be nothing to hinder a smooth voyage. A good omen.

The word inn painted a picture of travel, and willow is a homonym with the Chinese word "stay". When Chinese present a willow twig as a token for the traveller, it is an expression of not wanting to part company and hoping the traveller would stay a while longer.

Thus the first two verses of the poem seemed to have depicted rain and inn and willow but Wang was actually setting the stage using metaphors. He was supplying the prerequisite of the emotional content, priming our lachrymal ducts for what's to follow.

So let us say bottoms up to yet another drink, and how many drinks have we had? This is your last drink for a while, buddy, because soon you'll have no one to drink with. That's gut-wrenching!

Such is the desolate destitute, please, won't you stay for me? Don't go!

Wang ached.

Parting is such sweet sorrow is a line from Romeo and Juliet, expressing the affection between a man and a woman. In Wang's poem, there is resigned sadness, for a closeness soon to be beyond reach.

That was my inspiration for my paintings

I also tried painting just one camel, with Yang Pass much closer in the landscape, trying to describe the post-farewell stage of the journey, amplifying the solitude

The two versions side by side

Saturday, April 6, 2019

Who's being pedantic

I explored the availability of a power outlet during a painting demonstration planning session. I needed a hair dryer for my gig.

Chinese Brush painting is not unlike watercolor in some ways. We might be calling our techniques by different names but they are referencing the same principles. We are all dealing with the collective results of water, color and paper.

Xuan paper is the preferred paper we paint on and the absorbency of the paper is affected by whether it is sized or unsized with alum and the type of fibers that the paper is made from. The ability to control ink tone is one of the virtues we look for in a brush artist.

Feathering in watercolor involved forming a gradient that goes from saturated to more transparent by adding water to diffuse the color. In Chinese brush painting the diffusion can go both ways.

This is an example of saturated to light, or rich into light in our vernacular. The addition of ink or color onto a still wet brushstroke created the effect often employed for painting duckweed in Chinese painting

Clean water is applied around the hairline to promote ink diffusion, to make the brushroke more fluffy. It is not uncommon for Chinese Brush artists to hold two brushes in their hands, one with ink and the other one just a plain wet brush.

Here is an example of the opposite, light into rich. Brush with clean water is placed in still moist dark spots to create the voids

The following is an example of using stale ink ( the ink becomes more viscous due to evaporation, but the binder in the ink has also settled out somewhat ) The dark spot tends to stay put where as the water content from the ink seeps outward to form a clear margin.

An example of blooms by painting with coffee. This reminds me of water stain from a leaky roof. I

suspect the suspended fine coffee particles helped to create the dramatic border.

Unsized Xuan is more apt to record these gradients as the paper is more "indelible", relatively speaking. It traps all the nuances of a brushstroke. Sized or semi-sized paper on the other hand allows the ink or color to float a little bit longer before being latched on by the fibers, thus any gradients formed are usually more homogeneous and with smooth transition.

This is where my hair dryer comes into play. I use it for many reasons; hastening the drying time notwithstanding. Daft antics it is not. I use it as if it was the stop bath in the darkroom.

Anybody who has ventured into a photo darkroom knows to take the photo paper out of the developer once the ideal amount of silver grains are formed and move it to the acidic stop bath to halt the chemical reaction. Thus once I've attained an ideal diffusion or gradient with my ink or color, I would summon the power of heat and airflow to dry up my brushstroke to prevent further diffusion.

Thus instead of using a chemical, I use a tool; a hair dryer.

So my idea of using a hair dryer was not well received. People had no access to electricity or a hair dryer in the old days was the reason given.

To simply loathe the idea of borrowing from relevant technology is beyond me. Why must we pretend to be living in the past to be authentic. Does dressing up in faux period wardrobe make us more credible? Must we foster the stereotype of ancient Chinese to be convincing? Should we be luddites?

I'm sure name chop carvers didn't have access to power tools or computer aided graphics back in the old days. Should we be cooking our own soot and not use color dispensed from a tube when painting? So why the double standard. I mused, philosophically of course, how would the Witches Dance sound like in Berlioz's Symphonie Fantastique if violins were not allowed to be played col legno. How dare we strike the strings with the back of the bow?

For the eerie effects, your Honor!

A Duan inkstone was presented as a show and tell piece. The inkstone is produced from stones of Zhaoqing, Guangdong. Duan is the ancient name for today's Zhaoqing. Duan Yan ( Yan means inkstone in Chinese) is known for the fineness of its stone, thus it is not detrimental to the brush and for its ability to produce a nice ink suspension, given the right ink stick. Of course the ethereal workmanship and decoration motif must also be mentioned.

An expert immediately proclaimed that this inkstone can store ink overnight without the ink drying out and that it can produce 7 colors/tones of ink.

Chinese consider ink as a color, but the color of the ink refers to the different gradients and appearance of the ink spot. Thus the ink is dark, light, watery, scorched, or stale. Commonly the 5 colors are meant to remind us that we need to have variations in ink tones. Stale ink is interesting in that the ink is left out to evaporate and becomes more viscous. At the same time the binder in the ink settles out a bit so the resulting solution diffuses with a prominent clear margin around the dark area due to the less amount of binder in the solution. The contemporary paint Huang Binhong established the canon of 5 brushstroke methods and 7 ink colors. He added the interpretation of ink that is accumulated through repeated applications and scorched ink on a mostly dry brush to be written very slowly to allow the residue moisture from the brush to slowly seep out.

Thus the color/tone of the ink refers to how the ink is treated and applied and really has nothing to do with the inkstone per se. As far as storing the ink without it drying out, it has more to do with relative humidity and dew point and the porosity of the stone.

Invariably the conversation veers to the type of brush we paint with. The same expert gave some eyebrow raising comments. The brush hairs are from the "autumn hair" of animals, meaning the hair that animals/birds grew in autumn in anticipation of impending winter, he uttered. Autumn hair is a literal translation from the Chinese words 秋毫. It means fine long hair. It is used metaphorically to describe something that is minuscule and detailed. These 2 words are used in the context when a person discerningly examine details, the individual is examining autumn hair. A disciplined regiment who does not pilfer its citizens is said to not violate a single autumn hair. Someone who masters the brush art is said to have wicked beauty permeating to the tip of the autumn hair. It is plausible that such hair was employed for brush making in ancient history, or that the creme de la creme brush still uses such niche material, but to hype and exaggerate all Chinese brush as such is entirely unethical and not warranted. I think.

Of course the audience oohed and aahed in bewilderment.

Must we routinely mystify and embellish our art and implements in order to gain accreditation? Aren't the facts interesting and revealing by themselves? Are we living vicariously through these half truths to justify the present? Have we become snake oil peddlers?

Have I turned into a polemicist?

Who's being pedantic?

Chinese Brush painting is not unlike watercolor in some ways. We might be calling our techniques by different names but they are referencing the same principles. We are all dealing with the collective results of water, color and paper.

Xuan paper is the preferred paper we paint on and the absorbency of the paper is affected by whether it is sized or unsized with alum and the type of fibers that the paper is made from. The ability to control ink tone is one of the virtues we look for in a brush artist.

Feathering in watercolor involved forming a gradient that goes from saturated to more transparent by adding water to diffuse the color. In Chinese brush painting the diffusion can go both ways.

This is an example of saturated to light, or rich into light in our vernacular. The addition of ink or color onto a still wet brushstroke created the effect often employed for painting duckweed in Chinese painting

Clean water is applied around the hairline to promote ink diffusion, to make the brushroke more fluffy. It is not uncommon for Chinese Brush artists to hold two brushes in their hands, one with ink and the other one just a plain wet brush.

Here is an example of the opposite, light into rich. Brush with clean water is placed in still moist dark spots to create the voids

The following is an example of using stale ink ( the ink becomes more viscous due to evaporation, but the binder in the ink has also settled out somewhat ) The dark spot tends to stay put where as the water content from the ink seeps outward to form a clear margin.

An example of blooms by painting with coffee. This reminds me of water stain from a leaky roof. I

suspect the suspended fine coffee particles helped to create the dramatic border.

Unsized Xuan is more apt to record these gradients as the paper is more "indelible", relatively speaking. It traps all the nuances of a brushstroke. Sized or semi-sized paper on the other hand allows the ink or color to float a little bit longer before being latched on by the fibers, thus any gradients formed are usually more homogeneous and with smooth transition.

This is where my hair dryer comes into play. I use it for many reasons; hastening the drying time notwithstanding. Daft antics it is not. I use it as if it was the stop bath in the darkroom.

Anybody who has ventured into a photo darkroom knows to take the photo paper out of the developer once the ideal amount of silver grains are formed and move it to the acidic stop bath to halt the chemical reaction. Thus once I've attained an ideal diffusion or gradient with my ink or color, I would summon the power of heat and airflow to dry up my brushstroke to prevent further diffusion.

Thus instead of using a chemical, I use a tool; a hair dryer.

So my idea of using a hair dryer was not well received. People had no access to electricity or a hair dryer in the old days was the reason given.

To simply loathe the idea of borrowing from relevant technology is beyond me. Why must we pretend to be living in the past to be authentic. Does dressing up in faux period wardrobe make us more credible? Must we foster the stereotype of ancient Chinese to be convincing? Should we be luddites?

I'm sure name chop carvers didn't have access to power tools or computer aided graphics back in the old days. Should we be cooking our own soot and not use color dispensed from a tube when painting? So why the double standard. I mused, philosophically of course, how would the Witches Dance sound like in Berlioz's Symphonie Fantastique if violins were not allowed to be played col legno. How dare we strike the strings with the back of the bow?

For the eerie effects, your Honor!

A Duan inkstone was presented as a show and tell piece. The inkstone is produced from stones of Zhaoqing, Guangdong. Duan is the ancient name for today's Zhaoqing. Duan Yan ( Yan means inkstone in Chinese) is known for the fineness of its stone, thus it is not detrimental to the brush and for its ability to produce a nice ink suspension, given the right ink stick. Of course the ethereal workmanship and decoration motif must also be mentioned.

An expert immediately proclaimed that this inkstone can store ink overnight without the ink drying out and that it can produce 7 colors/tones of ink.

Chinese consider ink as a color, but the color of the ink refers to the different gradients and appearance of the ink spot. Thus the ink is dark, light, watery, scorched, or stale. Commonly the 5 colors are meant to remind us that we need to have variations in ink tones. Stale ink is interesting in that the ink is left out to evaporate and becomes more viscous. At the same time the binder in the ink settles out a bit so the resulting solution diffuses with a prominent clear margin around the dark area due to the less amount of binder in the solution. The contemporary paint Huang Binhong established the canon of 5 brushstroke methods and 7 ink colors. He added the interpretation of ink that is accumulated through repeated applications and scorched ink on a mostly dry brush to be written very slowly to allow the residue moisture from the brush to slowly seep out.

Thus the color/tone of the ink refers to how the ink is treated and applied and really has nothing to do with the inkstone per se. As far as storing the ink without it drying out, it has more to do with relative humidity and dew point and the porosity of the stone.

Invariably the conversation veers to the type of brush we paint with. The same expert gave some eyebrow raising comments. The brush hairs are from the "autumn hair" of animals, meaning the hair that animals/birds grew in autumn in anticipation of impending winter, he uttered. Autumn hair is a literal translation from the Chinese words 秋毫. It means fine long hair. It is used metaphorically to describe something that is minuscule and detailed. These 2 words are used in the context when a person discerningly examine details, the individual is examining autumn hair. A disciplined regiment who does not pilfer its citizens is said to not violate a single autumn hair. Someone who masters the brush art is said to have wicked beauty permeating to the tip of the autumn hair. It is plausible that such hair was employed for brush making in ancient history, or that the creme de la creme brush still uses such niche material, but to hype and exaggerate all Chinese brush as such is entirely unethical and not warranted. I think.

Of course the audience oohed and aahed in bewilderment.

Must we routinely mystify and embellish our art and implements in order to gain accreditation? Aren't the facts interesting and revealing by themselves? Are we living vicariously through these half truths to justify the present? Have we become snake oil peddlers?

Have I turned into a polemicist?

Who's being pedantic?

Labels:

autumn hair,

col legno,

Duan inkstone,

duckweed,

feathering,

hair dryer,

hector berlioz,

hype.,

ink colors,

ink tones,

luddite,

pedantic,

polemicist,

symphonie fantastique,

watercolor blooms,

witches dance

Sunday, March 31, 2019

Will Epsom Salt Work

I've used alum solution in my painting quite a bit. It is affectionately called the Ancient Chinese Secret Solution by me. Alum is used as a sizing agent for Xuan. I understand alum is used as a mordant in dying. I use it to function as a masking fluid by exploiting the fact that alum treated Xuan is less absorbent, thus the treated area will reveal with a different gradient when stained.

I typically would paint on the back side of the paper with a alum infused brush. The brushstroke will reveal a clear margin when a different color is painted over it; as long as that color is not too strong to obscure the margin.

Here's an example of the margin

I've also used this technique to create a blurry image by first painting with alum on the reverse side of the paper, allowing the brushstroke to show through the top side. I then go over the top side with a darker color, being careful to not totally obscure the original brushstroke on the back side. The resulting image has that interesting back lit effect and suggests a 3 dimensional perception, especially when viewed from a distance, or by squinting one's eyes.

Here's another example of painting done with alum solution. Its role in making the paper less absorbent is exploited to the extreme by functioning as a masking fluid. It was used to paint in the snow. Obviously it is well suited for high contrast work like this one.

I was contemplating painting a desert scene and I was interested in a novel way to depict the wind generated ridges on the sand dunes. I didn't want to paint these wavy ridges with hard ink brushstrokes. I therefore turned to my secret solution and envisioned the clear margins left by such brushstrokes would be more enigmatic and evoke more drama in my painting.

But I ran out of my Ancient Chinese Secret Solution.

I resorted to my daft antics.

I recall a leftover bag of Epsom salt from when I sprained my ankle. Epsom salt is magnesium sulfate. Could I substitute Epsom Salt for Alum, which is aluminum and potassium sulfate. I recall reading about using copper sulfate as a mordant, so why not magnesium sulfate?

I rolled up my sleeves and went to work. I prepared a saturated solution of Epsom salt. My experiment involved painting with the Epsom salt solution in raw and semi-sized Xuan. I painted on the top side of the paper, and on the back side of the paper to see if the reveal is different.

Here is the result of painting on regular raw Xuan. The top image is painting the Epsom salt solution on the top side of paper; bottom image is painted on the back side.

Here is the result of painting on semi-sized Xuan. This paper is less apt to absorb liquid because of the sizing, therefore I wanted to see what effect my concoction will have, if any.

So when applied to the top side of the semi-sized Xuan (top image) Epsom salt seems to have a smidgen of effect. I think I can make out a semblance of a faint margin.

As you can see, Epsom salt solution failed as a candidate for alum substitution.

I know what will be on my shopping list now.

I typically would paint on the back side of the paper with a alum infused brush. The brushstroke will reveal a clear margin when a different color is painted over it; as long as that color is not too strong to obscure the margin.

Here's an example of the margin

I've also used this technique to create a blurry image by first painting with alum on the reverse side of the paper, allowing the brushstroke to show through the top side. I then go over the top side with a darker color, being careful to not totally obscure the original brushstroke on the back side. The resulting image has that interesting back lit effect and suggests a 3 dimensional perception, especially when viewed from a distance, or by squinting one's eyes.

Here's another example of painting done with alum solution. Its role in making the paper less absorbent is exploited to the extreme by functioning as a masking fluid. It was used to paint in the snow. Obviously it is well suited for high contrast work like this one.

I was contemplating painting a desert scene and I was interested in a novel way to depict the wind generated ridges on the sand dunes. I didn't want to paint these wavy ridges with hard ink brushstrokes. I therefore turned to my secret solution and envisioned the clear margins left by such brushstrokes would be more enigmatic and evoke more drama in my painting.

But I ran out of my Ancient Chinese Secret Solution.

I resorted to my daft antics.

I recall a leftover bag of Epsom salt from when I sprained my ankle. Epsom salt is magnesium sulfate. Could I substitute Epsom Salt for Alum, which is aluminum and potassium sulfate. I recall reading about using copper sulfate as a mordant, so why not magnesium sulfate?

I rolled up my sleeves and went to work. I prepared a saturated solution of Epsom salt. My experiment involved painting with the Epsom salt solution in raw and semi-sized Xuan. I painted on the top side of the paper, and on the back side of the paper to see if the reveal is different.

Here is the result of painting on regular raw Xuan. The top image is painting the Epsom salt solution on the top side of paper; bottom image is painted on the back side.

Here is the result of painting on semi-sized Xuan. This paper is less apt to absorb liquid because of the sizing, therefore I wanted to see what effect my concoction will have, if any.

So when applied to the top side of the semi-sized Xuan (top image) Epsom salt seems to have a smidgen of effect. I think I can make out a semblance of a faint margin.

As you can see, Epsom salt solution failed as a candidate for alum substitution.

I know what will be on my shopping list now.

Tuesday, March 26, 2019

Project Water continued

Now that I had a chance to look at my water painting for a couple of weeks, I saw a major fault with the painting. I showed too much detail in the dark areas and no details at all in the blue areas. Instead of depicting contrast, a sunken feeling of imbalance was forged.

I know my motivation was curiosity, something to do, something to try so I should keep stoking that fire. My first mental sketch was for something that is impressionistic, nondescript and yet able to present a clear image of the subject matter. Perhaps I was trying to invent a Rorschach blot? Could it be that I have a very misguided understanding of pointillism and was trying to adulterate that with my experimentation?

Time to throw logic to the wind and grab my brush and ameliorate the experiment. Not the time to be pensive.

Basically I was writing in a lot more information, not only in the blue sections, but all over the paper. I was juxtaposing my blue lines with my ink lines, hoping that as they intersect, some of the crossings would be serendipitous, creating those short lines that I was looking for in the first place. I was so consumed by that process that I didn't want to disrupt that rhythm by snapping a photo to document the progress. Not even when I had to switch brushes.

So here's the new face, or phase, of my water project.

I know my motivation was curiosity, something to do, something to try so I should keep stoking that fire. My first mental sketch was for something that is impressionistic, nondescript and yet able to present a clear image of the subject matter. Perhaps I was trying to invent a Rorschach blot? Could it be that I have a very misguided understanding of pointillism and was trying to adulterate that with my experimentation?

Time to throw logic to the wind and grab my brush and ameliorate the experiment. Not the time to be pensive.

Basically I was writing in a lot more information, not only in the blue sections, but all over the paper. I was juxtaposing my blue lines with my ink lines, hoping that as they intersect, some of the crossings would be serendipitous, creating those short lines that I was looking for in the first place. I was so consumed by that process that I didn't want to disrupt that rhythm by snapping a photo to document the progress. Not even when I had to switch brushes.

So here's the new face, or phase, of my water project.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)